From this year, Scottish primary schools will be obliged to gather educational data for the government through ‘national assessments’ of P1, P4 and P7 children. This development comes at a time of considerable debate about the efficacy of national testing in general and its potential link to increases in mental health problems among children and young people. Accordingly, in May this year the UK Parliamentary Education Committee recommended significant changes to England’s assessment regime.

Testing at P1 is particularly controversial. The younger children are, the more likely it is that ‘adverse experiences’ will affect their long-term development. Given the body of evidence against national standardised testing at this age (as outlined below), Upstart urges the Scottish government to abandon plans to test children during their first year in school.

1. Standardised ‘baseline’ testing of four- and five-year-olds is not reliable. In 2016, wide variations were found in children’s scores on three baseline tests from accredited test providers (the National Foundation for Educational Research, Durham University’s Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring [CEM] and Early Excellence). An attempt to introduce baseline testing in England was dropped and the Parliamentary Education Committee mentioned above recommended that any measurement in the first year of schooling should be by teacher assessment only.

2. Testing can create self-fulfilling prophecies, which are particularly damaging at very beginning of a child’s school career. Four- and five-year-old children are at a stage in development when performance on a test can vary from day to day (see second item in this newspaper report).

3. Throughout the world, the introduction of national testing has resulted in ‘teaching to the test’. This leads to a narrowing of the curriculum and uninspiring teaching methods, which are designed to achieve good test results, but do so at the expense of deeper learning. It is particularly detrimental in P1 (see 4, below).

4. There is a wealth of research showing that four- and five-year-old children

learn best through play and other holistic learning experiences. Tests, however, require them to focus on specific abstract ideas which often seem pointless to young children and can therefore easily be misunderstood. Time spent on testing and preparing children for tests is therefore highly counterproductive, at a stage in their lives when their lifelong attitude to learning is still developing.

learn best through play and other holistic learning experiences. Tests, however, require them to focus on specific abstract ideas which often seem pointless to young children and can therefore easily be misunderstood. Time spent on testing and preparing children for tests is therefore highly counterproductive, at a stage in their lives when their lifelong attitude to learning is still developing.

5. Primary 1 is traditionally a ‘settling in’ year for children, when teachers focus on their social and emotional development. Since the transition between nursery/home and school is deeply significant for four- and five-year-olds, it is naturally a stressful experience and children who do not settle easily may become disengaged from learning. This means that their relationship with their teacher is of paramount importance, particularly if they are encountering stress in other aspects of their lives. The quality of this relationship is bound to be affected if the teacher is required to ensure that children attain academic standards specified by the tests and related benchmarks.

6. Assessment at P1 is being introduced as part of a drive to ‘close the attainment gap between rich and poor’. Although a narrow focus on specific literacy and numeracy skills can undoubtedly raise test scores among disadvantaged children in the short term, research shows that such improvements ‘wash out’ over the course of their primary education. On the other hand, it has been shown that early academic instruction can have other – highly damaging – long-term consequences for disadvantaged children.

7. Due to significant lifestyle changes over recent decades, most children starting school today have had far fewer opportunities for active, self-directed play than in the past (particularly outdoor play). Over the same period, there have been significant increases in mental health problems among children and young people. It is well established that resilience (the ability to cope with stress throughout life) is developed through a combination of play and supportive relationships in the early years. The effects of testing on the EY curriculum and the requirement that P1 teachers work towards specific skills-based standards (as opposed to supporting individual development) therefore has implications for many children’s well-being in the future.

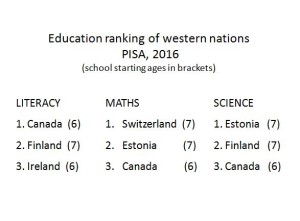

8. Testing affects public perceptions about education, not least because of the media coverage it generates. Tests for four- and five-year-olds will intensify the widely-held misconception that children of this age must reach certain standards in literacy and numeracy. In fact, there is no evidence that an early start on the three Rs is necessary or, indeed, beneficial. Research in New Zealand showed that when literacy skills-teaching began when children were seven, they were as efficient readers by the age of 11 as those who started at five. Indeed, in the vast majority of countries  worldwide, children do not even start school until they are at least six years old. Until then they go to kindergarten and learn at their own rate, following their own interests through play. When young children learn through play they discover that learning is fun.

worldwide, children do not even start school until they are at least six years old. Until then they go to kindergarten and learn at their own rate, following their own interests through play. When young children learn through play they discover that learning is fun.

9. Tests are not fun. They are not play. And they do not have a place in the lives of four- and five-year-old children. We’ve heard it said that ‘The P1 tests are more like a computer game than a test – children won’t even know they’re being tested!’ But children are not stupid. They can tell when the grown-ups are judging them. They recognise adult priorities. There now is widespread concern among experts in early child development (and other related academic and professional fields) about the long-term effects on health and well-being of an overly-academised, high-pressure childhood.

10. The introduction of national testing has been driven by political – not educational – considerations. It is at odds with the play-based pedagogical principles underpinning the Early Level of the Curriculum for Excellence and explained in greater detail in Building the Curriculum 2 (2007). Unfortunately, the integration of these principles into P1 teaching practice has so far been extremely patchy. Their importance has, however, been confirmed by all recent early years research and, over the last couple of years, there’s been increased commitment among P1 teachers to the introduction of play-based practice. It’s highly unlikely that this welcome development will continue if teachers feel obliged to adapt their practice to ensure children’s success in skills-based tests.

10. The introduction of national testing has been driven by political – not educational – considerations. It is at odds with the play-based pedagogical principles underpinning the Early Level of the Curriculum for Excellence and explained in greater detail in Building the Curriculum 2 (2007). Unfortunately, the integration of these principles into P1 teaching practice has so far been extremely patchy. Their importance has, however, been confirmed by all recent early years research and, over the last couple of years, there’s been increased commitment among P1 teachers to the introduction of play-based practice. It’s highly unlikely that this welcome development will continue if teachers feel obliged to adapt their practice to ensure children’s success in skills-based tests.

The aim of the Upstart Scotland campaign is to create a ‘ring-fenced kindergarten stage’ for three- to seven-year-old children based on these well-established pedagogical principles. This would ensure that all Scottish children have at least three years during early childhood to reap the developmental benefits of play (as often as possible outdoors and in natural surroundings) while being sensitively supported to learn at their own pace, rather than being judged against arbitrarily-determined academic standards.