by Anne McKechnie

At 14 years old Kathy had an ACE score of seven – her experiences included physical neglect and abuse, emotional neglect and abuse, sexual abuse at the hands of her father and his peers, frequent exposure to domestic violence between her mother and her partners. In addition, her mother had substance misuse and mental health problems and her parents separated when she was a toddler.

With increasingly unmanageable and aggressive behaviours, she was placed in a children’s home where she was sexually abused and, when she absconded to escape threat, was sexually abused by older men. Only at 16 years old was Kathy able to disclose her abuse. Until then, she was labelled as “mentally ill”, presenting with “developmental disorders” and “resistant” to support or intervention.

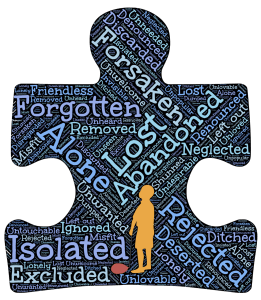

Kathy’s view of herself was that she was dirty; she was to blame for everything that had happened, no one would ever care for her, the world was unsafe and she would always have to fight.

I have practiced as a forensic and clinical psychologist for over 35 years. In clinical practice from outpatient to inpatient mental health services, secure facilities for all ages and those with mental illness, I have noted the almost ubiquitous presence of childhood experiences of abuse and neglect. Impact is evident in the development of coping strategies such as substance misuse and addiction, offending behaviour, mental illness, self-harm and a vulnerability to repeat victimisation.

In 2008,  the Scottish Government introduced Routine Sensitive Inquiry in the National Health Service in Scotland (C.E.L. 41, 2008). This recognised the high prevalence of gender-based violence and history of childhood abuse in patients presenting with mental health and addictions services. As a result, questions about early childhood trauma should be asked routinely in all mental health assessments. The original aim was to include such questions in all health appointments but attempts to encourage colleagues in physical health to do so were met with a level of anxiety.

the Scottish Government introduced Routine Sensitive Inquiry in the National Health Service in Scotland (C.E.L. 41, 2008). This recognised the high prevalence of gender-based violence and history of childhood abuse in patients presenting with mental health and addictions services. As a result, questions about early childhood trauma should be asked routinely in all mental health assessments. The original aim was to include such questions in all health appointments but attempts to encourage colleagues in physical health to do so were met with a level of anxiety.

Hence, when the ACE research was published, mental health and criminal justice professionals were not surprised at the findings but welcomed the media and societal awareness which burgeoned interest in this oft neglected area.

But, why were we mental health practitioners not revealing and sharing these clinical insights earlier and raising public awareness as Felitti, did? What stopped us? Could it be stigma and shame mirroring that frequently reported by survivors of abuse and adversity?

Mental illness, poor mental health, addictions and offending and, most disturbingly, children in care are areas rife with stigma and judgement. Unlike physical illness, an individual who is severely depressed, imprisoned for violence or is addicted to heroin is often seen as culpable, to have “chosen” that path and, worst of all, may “infect” the rest of us. Sympathy and compassion offered to those with severe physical illness is rarely available to chronic mental health patients, children in care or offenders.

Has this stigma and lack of compassion stopped mental health and criminal justice workers sharing our knowledge of the link between childhood adversity and mental illness or criminality? We know that toxic stress leads to high levels of the stress hormone cortisol, which is turn impacts on the immune system; hence leading to increased risk of certain physical conditions. The risk of physical illness is also increased as people try to cope by using drink and drugs, smoking or over-eating.

While the impact of childhood trauma on physical health is concerning, in my opinion the impact on lifestyle and life choices is worse. Studies have shown that a score of 4 or more ACEs leads to heightened risk of serious offending, alcohol and substance misuse and serious mental health problems; double the risk of serious health problems. These are problems affecting our criminal justice and mental health systems, but also the ability of an individual to lead a fulfilling and satisfying life.

Such statistical associations cannot be attributed solely to biology. The key is in how survivors of childhood trauma interpret or make sense of their experiences; where someone blames themselves for adversity, they will believe they are worth little. Failure to understand and acknowledge this point risks offering the message that poor health and poor social outcomes are inevitable where there is adversity, thereby removing from our most vulnerable individuals the most valuable emotion of hope.

When a child is supported to see that abuse is not their fault, that they deserve better and that adults can be trusted to keep them safe, only then can they build the buffering relationships referred to in the ACE literature. If , however, systems take the view that you, as a child, are unmanageable, unlovable, “place yourself at risk” and subsequently remove you repeatedly through several establishments, these core beliefs will be exacerbated. No child with such beliefs can be expected to build the trust essential to building healing relationships. It is this interpretation of early adversity that in my view is crucial to the development of psychological and social impact of ACES.

, however, systems take the view that you, as a child, are unmanageable, unlovable, “place yourself at risk” and subsequently remove you repeatedly through several establishments, these core beliefs will be exacerbated. No child with such beliefs can be expected to build the trust essential to building healing relationships. It is this interpretation of early adversity that in my view is crucial to the development of psychological and social impact of ACES.

The ACE movement has afforded us all the opportunity to talk openly about ACES – the stigma of childhood abuse and trauma is being removed by such open talk. However, it is important that we do not underestimate the difficulty in facilitating children and young people to build buffering relationships. It is only by identifying and challenging core beliefs around abuse, that we can begin to challenge the sense that poor health and social outcomes are inevitable.

Kathy’s process of healing can only start when we in society acknowledge the reality of failing to protect her – that her safety as a child was our responsibility and she should have been protected. This message repeated continually and reflected in how she is treated by society can help challenge and change her core belief of shame, guilt and undeserving to one of hope and trust in a valued place in society.

Kathy’s process of healing can only start when we in society acknowledge the reality of failing to protect her – that her safety as a child was our responsibility and she should have been protected. This message repeated continually and reflected in how she is treated by society can help challenge and change her core belief of shame, guilt and undeserving to one of hope and trust in a valued place in society.