by Sue Palmer

Scarcely a day goes by without media stories about the ‘child and adolescent mental health crisis’. It seems our young people – especially girls – find life increasingly stressful. This month, for instance, a Scottish Government survey found that more than a third of S4 girls have “very high” emotional problems, compared to 11% of boys.

As usual, the researchers blamed the problem on teenage culture, concluding that “it is possible that the widening inequality in emotional well-being is partly influenced by differences in how adolescent boys and girls tend to engage with social media.” Girls use photo-based platforms more than boys and “compare themselves more to others they see on social media.”

As usual, the researchers blamed the problem on teenage culture, concluding that “it is possible that the widening inequality in emotional well-being is partly influenced by differences in how adolescent boys and girls tend to engage with social media.” Girls use photo-based platforms more than boys and “compare themselves more to others they see on social media.”

It’s a worrying conclusion because social media are undoubtedly here to stay. Indeed, all 21st century stress factors are more likely to increase than to decrease. If, as recorded in the same survey, only 6% of S4 girls and 14% of boys have high positive mental well-being, the outlook for future generations seems bleak.

This is why Upstart Scotland argues that best way to tackle the mental health crisis is to focus on developing long-term emotional resilience – the human characteristic that helps us deal with stress and rise to challenges. In previous blogs and newsletters, we’ve recorded a growing mountain of research showing that the critical period for developing resilience is early childhood and that – particularly up to the age of seven – the two essential ingredients are love and play. If we want children to grow into resilient young people, we must give them time simply to enjoy being children, rather than sending them to school at the age of four or five.

Here’s looking at you, kid

But why should our early start on formal schooling damage girls’ mental health more than boys? Some years ago, while researching and writing my book ‘21st Century Girls’ I concluded that it’s due to little girls being generally more socially self-conscious than boys. And it all starts in the womb.

But why should our early start on formal schooling damage girls’ mental health more than boys? Some years ago, while researching and writing my book ‘21st Century Girls’ I concluded that it’s due to little girls being generally more socially self-conscious than boys. And it all starts in the womb.

For complex biological reasons, female embryos develop slightly faster than males so newborn girls are generally a little better than boys at controlling their behaviour. This means they find it easier to maintain eye-contact with their adult carer.

All newborns are programmed by nature to gaze into the eyes of the adults who care for them – it’s a key element in the formation of strong attachment bonds, which underpin successful emotional development. As explained in this recent TESS article, children’s long-term emotional resilience depends to a great extent on their feeling ‘loved and lovable’.

According to research, over the first four months of life girls’ ability to make eye contact improves on average by four hundred per cent, which is good news for their attachment potential and social development. Most boys, being more excitable and distractable, make little or no improvement over that period. As time goes on, their social kick-start means girl babies are generally quicker than boys at all aspects of social learning, such as imitating facial expressions, raising their arms to be picked up and cuddled, waving bye-bye and learning to talk.

By the time they start school, girls are therefore better adapted for settling down in a classroom and conforming to their teacher’s requests than their male counterparts, which has resulted in a female edge in overall academic achievement that now lasts right through the education system.

Daring ventures from a secure base

But early sociability is a double-edged sword. Research has also found that, by the age of one, girls check their carers’ faces for signs of approval four times as often as boys. They’re therefore more likely to adjust their behaviour to please their carers – and if the carers are risk-averse, they’ll gradually become risk-averse too. If an early yearning for social approval turns children into ‘people-pleasers’, it easily leads to excessive compliance and over-reliance on current social norms.

But early sociability is a double-edged sword. Research has also found that, by the age of one, girls check their carers’ faces for signs of approval four times as often as boys. They’re therefore more likely to adjust their behaviour to please their carers – and if the carers are risk-averse, they’ll gradually become risk-averse too. If an early yearning for social approval turns children into ‘people-pleasers’, it easily leads to excessive compliance and over-reliance on current social norms.

In a country like Scotland, where formal schooling starts at age four or five, this is a particular danger. Very few children of that age have well-developed self-regulation skills (see The Importance of Being Five) so the desire for teacher approval encourages compliance, especially in socially-aware little girls. It may also lead to constant stress, as the child strives to earn rewards (ticks, stickers, smiley faces) and avoid punishment (being told off) rather than feeling ‘loved and lovable’ for what she is – a very young child, who needs a caring attachment figure.

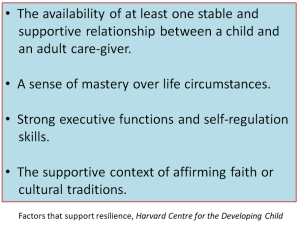

What’s more, secure attachment isn’t the only factor involved in long-term resilience. As the Harvard Centre for the Developing Child tells us (see panel), children’s sense of mastery, along with developing the capacity for executive function and self-regulation, are also significant. During early childhood all these are developed through self-directed play.

What’s more, secure attachment isn’t the only factor involved in long-term resilience. As the Harvard Centre for the Developing Child tells us (see panel), children’s sense of mastery, along with developing the capacity for executive function and self-regulation, are also significant. During early childhood all these are developed through self-directed play.

For most of human history, young children played for most of the day until they were about seven, when they were considered old enough to help with their parents’ work (or, in wealthy families, for education) – and even then they played whenever they had free time.

Once universal compulsory schooling began they played until starting school, and then at weekends, during holidays and around the edges of every school day. They played outdoors, with other children, without much interference from adults or much particular equipment beyond what they found lying around. Indeed, going out to play – along with the loving care of adults – was the ‘supportive culture’ available to all lucky children through the millennia – until the latter decades of the twentieth century.

John Bowlby, the founder of attachment theory, summed up the symbiotic relationship between love and play thus: ‘Life is best organised as a series of daring ventures from a secure base.’ From around age three, a securely-attached child can venture off to play with her peers, thus developing a wide variety of skills and capacities that will support lifelong well-being (and, incidentally, educational success). But seismic changes to childhood’s ‘supportive culture’ over the last fifty years have been accompanied by a steady increase in developmental and mental health problems.

Taking the long view

Even though girls’ social precocity has turned out to be an advantage in terms of school-based learning, educational success based on the need to please the teachers doesn’t prove as beneficial in the long-term as a genuine thirst to learn. A girl with an ingrained yearning to conform to social norms is also at a serious disadvantage in the 21st century maelstrom of adolescent social media. She’ll be under constant stress as she views the apparent ‘perfection’ of other girls’ social lives and finds her own seriously wanting.

There are many other cultural sources of stress. For instance, in a hyper-consumer culture, socially-sensitive females are likely to be fashion-victims, constantly in pursuit of the elusive products that could transform their lives (particularly stressful if they’re from a family that can’t afford the goods). And now that children generally discover internet pornography at around the age of thirteen, they’re likely to be anxious about aspects of their body and highly confused about sexual relationships.

There are many other cultural sources of stress. For instance, in a hyper-consumer culture, socially-sensitive females are likely to be fashion-victims, constantly in pursuit of the elusive products that could transform their lives (particularly stressful if they’re from a family that can’t afford the goods). And now that children generally discover internet pornography at around the age of thirteen, they’re likely to be anxious about aspects of their body and highly confused about sexual relationships.

21st century girls need deep reserves of emotional resilience as much as (perhaps more than) previous generations. So during early childhood they need to play, engaging in real-life experiences, in real time and space.

Girls who feel at home in the real world at this formative age are much more likely to want to get outdoors and active as they grow older. They’ll also be better fitted to to question the unrealistic norms of virtual reality.

Girls also need time and space during early childhood to develop healthy social skills – learning get along with others on their own terms, to choose friends wisely and cope with fall-outs. And for long-term resilience, they need plenty of opportunities to run, jump, climb, build, explore, experiment and take the sort of play-based risks that test their skills. In the words of Lady Allen of Hurtwood, an early exponent of adventure playgrounds, ‘Better a broken bone than a broken spirit!’

Reimagining childhood

Tragically, this kind of self-directed, active, outdoor play has more-or-less disappeared from most young children’s lives. In 21st century Scotland, it’s almost impossible for most parents to provide the freedom to play as children have played in the past. That’s why Upstart Scotland campaigns for a change to universal state services during early childhood.

A relationship-centred, play-based kindergarten stage for three- to seven-year-olds (with plenty of time spent outdoors) would benefit girls just as much as boys – indeed, perhaps more. Here they can learn that it’s OK to engage in ‘daring ventures’ of discovery, rather than the anxious pursuit of ticks, stars or smiley faces. A well-run kindergarten, with well-qualified staff who understand the value of attachment and play, provides exactly the type of secure base in which all under-sevens can develop their full potential.

A relationship-centred, play-based kindergarten stage for three- to seven-year-olds (with plenty of time spent outdoors) would benefit girls just as much as boys – indeed, perhaps more. Here they can learn that it’s OK to engage in ‘daring ventures’ of discovery, rather than the anxious pursuit of ticks, stars or smiley faces. A well-run kindergarten, with well-qualified staff who understand the value of attachment and play, provides exactly the type of secure base in which all under-sevens can develop their full potential.

I don’t think it’s any coincidence that the Nordic countries, which have provided this type of kindergarten experience for many decades, have the highest levels of childhood well-being in the world – and the best record for gender equality. Little girls, just like their brothers, really do need to have fun.