by Alison Whelan

In late 2020 I became so unwell I was forced to go on long term sickness absence from my job as a lead early years teacher. Over the following months it became clear that the cause of my illness was work-related stress.

Twenty-two years earlier, following a traumatic life event, I’d learned about the effects of stress on the human body of both adults and infants – something I was not taught during my early years teacher training at university. At the time of this trauma, I had two children under three, so I needed to learn quickly for their sakes. Over the following years I had made major life changes to reduce stress, so I was sad that they hadn’t saved me from succumbing to work-related stress.

What I hadn’t appreciated is that the body remembers stress and so a series of events over the last 16 months combined with that previous trauma to trigger my illness. It has taken me many months to become well again and for me to understand that I could not return to the job that I loved. I resigned from my post in the summer term this year. This is the first September in 30 years I have not started a new school year working in the English state education system.

Stress in the early years

In my experience the working environment that exists in the English state education system is a stressful one. This has been acknowledged by the lip service currently being paid to staff ‘wellbeing’ and the insidious use of the word ‘resilience’ in relation to both staff and pupils by Ofsted.

For many years working as a reception (P1) teacher, I thought that most of the stress I was under came from the exhausting effort of explaining to people, both in and out of school about the absolute necessity of supporting children’s learning in a developmentally appropriate way.

For many years working as a reception (P1) teacher, I thought that most of the stress I was under came from the exhausting effort of explaining to people, both in and out of school about the absolute necessity of supporting children’s learning in a developmentally appropriate way.

I would talk about how formal schooling at four had nothing to do with a child’s development but was a vestige of policies started in the Industrial Revolution; the success of Scandinavian education where there is no formal schooling until 7, and how science tells us that children learn optimally for their present and for their future selves through self-directed play alongside adults who are highly trained in the science of relationships, connection, and child development.

This felt like a yearly fight to protect the developing brains and bodies of the very young children in my care, followed by the feelings of helplessness, anger and sadness for the children and their families I’d worked with, when they left reception for the formality of Year One (P2). For sure, all of my colleagues were highly skilful, caring, and supportive professionals for whom I had the upmost respect. But even though the words ‘play-based’ and ‘child-led’ were integral to our policies and in daily use, there seemed to be a disconnect between such language and what adults were expected to be doing with children.

This felt like a yearly fight to protect the developing brains and bodies of the very young children in my care, followed by the feelings of helplessness, anger and sadness for the children and their families I’d worked with, when they left reception for the formality of Year One (P2). For sure, all of my colleagues were highly skilful, caring, and supportive professionals for whom I had the upmost respect. But even though the words ‘play-based’ and ‘child-led’ were integral to our policies and in daily use, there seemed to be a disconnect between such language and what adults were expected to be doing with children.

Pencil grip, phonics, and children being able to ‘sit still and listen’ were the kinds of things that were given priority: specific knowledge and skills to fill children up with. This did not feel like the pedagogy I wanted to nurture. However, it did feel familiar and somehow safe, so on some level acceptable.

From primary to nursery

I came to realise it felt like that because that was the dominant pedagogy I experienced as a child growing up in the 1970s. Just like my attachment style, which I had been exploring since the trauma I experienced two decades before, I began to understand that I also needed to examine my ‘pedagogy style’ – what had been done to me when I was in school?

Once I had done this, the realisation hit me that I could not continue to work in a primary school and remain emotionally regulated. I decided to make the move to working in a maintained nursery school. I thought I could carry on ‘the fight’ from there, free from the system that dictated such harmful things as baseline assessments, phonics screening tests and SATS.

Once I had done this, the realisation hit me that I could not continue to work in a primary school and remain emotionally regulated. I decided to make the move to working in a maintained nursery school. I thought I could carry on ‘the fight’ from there, free from the system that dictated such harmful things as baseline assessments, phonics screening tests and SATS.

I was lucky, I always did well when observed by SLT and in Ofsted inspections, so there was respect for how I did things and for a few years things went well. The feeling of fighting a system was ever present, but with some of my new dedicated, curious, and highly competent colleagues we developed a way of working alongside children and their families that respected child developmental processes and crucially, how to respond to those processes. I became a trainer and supported colleagues across my Local Authority, I delivered CPD and wrote a couple of articles for a professional journal about how we responded to developmental processes happening in young children at our nursery.

If the pandemic had not happened, I think I would still be there, fighting alongside my colleagues for maintained nursery schools which I believed represented the last place of safety for an early years education system that genuinely accepted the science of how an adult’s behaviour affects the developing brains and bodies of young children.

Following the science…

Even before the pandemic it was hugely challenging for adults to remain emotionally regulated due to issues created by such things as chronic underfunding, and the closure threat to maintained nursery schools. But, in the months following March 2020, Government policy directly led to the complete abandonment of even the tokenism that had been paid to respecting the science of child development in the past.

Even before the pandemic it was hugely challenging for adults to remain emotionally regulated due to issues created by such things as chronic underfunding, and the closure threat to maintained nursery schools. But, in the months following March 2020, Government policy directly led to the complete abandonment of even the tokenism that had been paid to respecting the science of child development in the past.

This was illustrated most notably to me by witnessing children being taken from their masked parent at the door of the nursery school after waiting in a socially distanced queue. I knew what language such as ‘lost learning’ and ‘catch-up’ coming from the Department for Education really meant for children, families and anyone working in schools. All of this was the tipping point, and the stress reached such a point that my body said ‘no’.

I have nothing but admiration for those people working full time in the current English education system who can be that emotionally regulated educator (who has explored their own attachment and pedagogy style) working alongside children and their families. But it is my fear that those people are rare and all I can see is adults struggling each day to remain emotionally regulated and, whilst they are battling against stress and anxiety, unintentionally damaging the next generation in a never ending cycle.

I now understand that the most stressful part of working in early years education has been knowing about the science of child development, whilst simultaneously being part of a system whose policies mean that science is ignored. Being asked in effect to knowingly damage children’s developing brains and bodies, and the consequences of the decision to refuse to do so, was not a good place to be for my mental health. Being in that situation caused me significant emotional and physical stress, and I can now see, after months of being out of the system, why it has taken me so long to articulate the cause of this stress.

I now understand that the most stressful part of working in early years education has been knowing about the science of child development, whilst simultaneously being part of a system whose policies mean that science is ignored. Being asked in effect to knowingly damage children’s developing brains and bodies, and the consequences of the decision to refuse to do so, was not a good place to be for my mental health. Being in that situation caused me significant emotional and physical stress, and I can now see, after months of being out of the system, why it has taken me so long to articulate the cause of this stress.

It is an illusion that I felt I was ‘fighting the system’ by continuing to struggle for a place where children and families would find educators who understood the science of child development and the importance of relationships. Because the ‘fight’ was with the systems in my own body. For all the reasons I’ve described in this piece, I suspect this is the case for many professionals working in education.

Looking to Scotland…

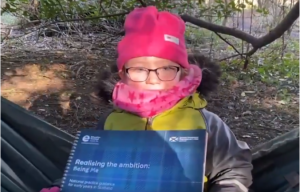

However, I do feel a renewed optimism! Over the last few years my eyes have turned to Scotland, to the truly joyous practice guidance (Realising the Ambition; Being Me) and to the work of Upstart, Dr Suzanne Zeedyk, and many more. From where I am in England, I see in Scotland a powerful, creative movement rooted in an authentic understanding of the science of human biology.

However, I do feel a renewed optimism! Over the last few years my eyes have turned to Scotland, to the truly joyous practice guidance (Realising the Ambition; Being Me) and to the work of Upstart, Dr Suzanne Zeedyk, and many more. From where I am in England, I see in Scotland a powerful, creative movement rooted in an authentic understanding of the science of human biology.

From this place of safety and wellness I find myself in now, I’m proud to add my voice to those of colleagues across the UK, championing the urgent call for change being made in Scotland.