by Sue Palmer

In August 2021 the Scottish government launched a consultation document about a National Care Service (NCS). It’s more extensive than England’s proposed provision of social care for the elderly because it covers all adult social care, with a suggestion that it should also include the care of looked-after children.

In August 2021 the Scottish government launched a consultation document about a National Care Service (NCS). It’s more extensive than England’s proposed provision of social care for the elderly because it covers all adult social care, with a suggestion that it should also include the care of looked-after children.

However, at no point is there any mention in the document of care for young children, including the newly expanded ELC sector (Early Learning and Care). In terms of a National Care strategy, this seems a serious oversight.

Who cares for young children?

High-quality care is, of course, central to children’s development, health and well-being, especially during early childhood (birth to eight years old) and over recent decades it has increasingly been provided by Scotland’s universal state services. Currently, the responsibility for monitoring the quality of ELC falls on the Care Inspectorate (CI) and Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC), as indeed does care provided by various services for children under the age of three, by childminders and by out-of-school care organisations, none of which are mentioned in the NCS consultation document.

High-quality care is, of course, central to children’s development, health and well-being, especially during early childhood (birth to eight years old) and over recent decades it has increasingly been provided by Scotland’s universal state services. Currently, the responsibility for monitoring the quality of ELC falls on the Care Inspectorate (CI) and Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC), as indeed does care provided by various services for children under the age of three, by childminders and by out-of-school care organisations, none of which are mentioned in the NCS consultation document.

If an adult-orientated National Care Service is established, it is very likely that remit of the CI and SSSC will change. Which government department will then be responsible for monitoring the quality of care during early childhood?

One possible scenario is that supervision of care for children between birth and three years will default to the Health Service and (since Curriculum for Excellence kicks in at age three) the care of three- to seven-year-olds will become the responsibility of the Education Department.

Another possibility is that the Scottish government could create a new Department for Early Years, to ensure developmentally-appropriate, rights-focused provision of state services for children between birth and eight.

Early childhood care and education (ECEC) versus Education

Upstart Scotland would be delighted if the Scottish government were to take the latter course. We would be horrified, however, if what the United Nations calls early childhood education and care (ECEC) were to become the responsibility of the Department for Education.

The aims of ECEC are admirably described by UNESCO in the statement below:

In order to achieve the aims listed by UNESCO, policy for education 3-7 should be devised – and practice supervised – by early years specialists (such as those who wrote Scotland’s recent practice guidance, Realising the Ambition: Being Me) because a developmental approach is guided by care for each child’s growth as a unique individual, with an emphasis on supportive relationships with caring adults and learning through play.

By contrast, educational policy and practice is generally influenced by age-related, standardised expectations for academic achievement, particularly in literacy and numeracy. Experience around the UK over the last two decades has clearly shown that, when ECEC is subsumed into the education sector, the advice of early years experts is ignored by the overwhelming majority of educationists, whose experience is with older age groups and who have little knowledge or understanding of early child development.

In Scotland, for instance, it is currently impossible for Primary 1 teachers to properly implement Realising the Ambition due to pressure to teach specific academic skills covered in the Scottish Standardised National Assessments of literacy and numeracy. The continued presence of national standardised assessments of these subjects in Primary 1 (despite significant professional opposition) illustrates the education establishment’s attachment to top-down pressure for inappropriate practice in early years.

In Scotland, for instance, it is currently impossible for Primary 1 teachers to properly implement Realising the Ambition due to pressure to teach specific academic skills covered in the Scottish Standardised National Assessments of literacy and numeracy. The continued presence of national standardised assessments of these subjects in Primary 1 (despite significant professional opposition) illustrates the education establishment’s attachment to top-down pressure for inappropriate practice in early years.

A government Department for Early Years

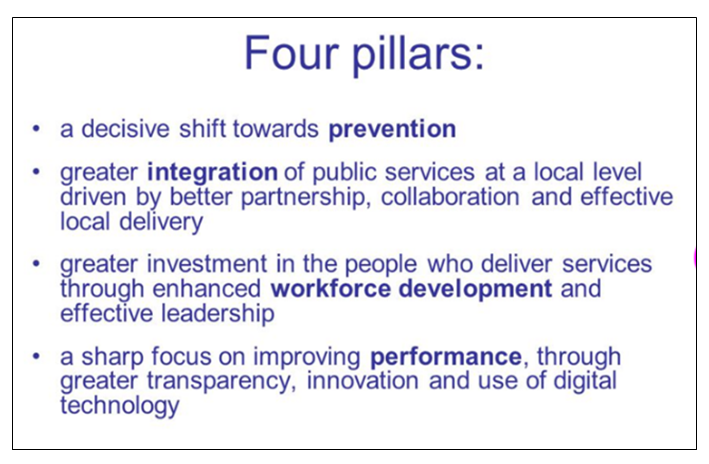

In 2011, the Christie Committee on Public Service called for ‘a decisive shift towards prevention‘ [of social, health and educational problems]. This year being Christie’s twentieth anniversary, there have been many articles bemoaning Scotland’s lack of success in abiding by the Four Pillars underpinning the committee’s aims:

It is widely agreed that Scotland’s public policy looks excellent on paper but falls sadly below standard in practice: the rhetoric does not match the reality. In terms of both care and education, we need something of a shake-up to revive Christie’s ambitions – something which also indicates that the incorporation of the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child into Scots law is more than a political flourish.

The introduction of an adult-oriented National Care Service provides Scotland with an opportunity to put a similar emphasis on early childhood care, thus making the ‘decisive shift’ towards prevention of problems with health, well-being and educational achievement in later years. A government Department for Early Years – operating across silos, informed by experts in early child development and driven by Christie’s Four Pillars – could transform policy and practice at national and local level, basing it on the latest international science and effective practice.

Whatever happens, Scotland must ensure that the introduction of a National Care Service does not side-line attention to the care of young children (by focusing instead on aspects of ‘health’ and/or ‘education’ rather than holistic development ).

Upstart Scotland is a campaign for a rights-focused, relationship-centred, play-based kindergarten stage (3-7 years) based on the Nordic model.