by Suzanne Axelsson

I am grateful to be able to observe children engaging with the world through play, making sense of it rooted in joy, exploring with a sense of wonder … and that I have permission to respond to that as the foundation of my teaching here in Sweden.

I am grateful to be able to observe children engaging with the world through play, making sense of it rooted in joy, exploring with a sense of wonder … and that I have permission to respond to that as the foundation of my teaching here in Sweden.

I refer to myself as a play-responsive pedagogue. The children’s play informs how I should respond as an educator, mostly referred to as “pedagogue” in Sweden, regardless of whether you are a trained teacher, care-worker or untrained.

My first full time position in a preschool in Sweden was in 1995, prior to the shift from Social Services to the Swedish Education Authority and the creation of the EY curriculum in 1998. Play is the way here, and I cannot imagine being a pedagogue in any other way, and I am extremely thankful that this was the system my own children grew up in.

The role of the pedagogue

I have the privilege to watch children’s self esteem grow as I step back and allow them to master physical, cognitive and emotional challenges while I am visibly invisible. It is common in Sweden to spend multiple years with a group of children, so by the time they are five you have known them for most of their lives, and the relationship of trust between the children and adult allows for that stepping back and trusting the play.

I trust the children, I know their capabilities, I understand how I can optimally challenge them without interference, I know when to step in – to scaffold, support or to comfort. I know how they play and learn. More importantly, the children trust me; they know that I will not interfere when they are deep in play, so my presence does not disturb, they know I will plan meaningful things for them, they know I will listen to their ideas, opinions and objections fairly. They also trust each other. We have created a community of play and learning where everyone is valued.

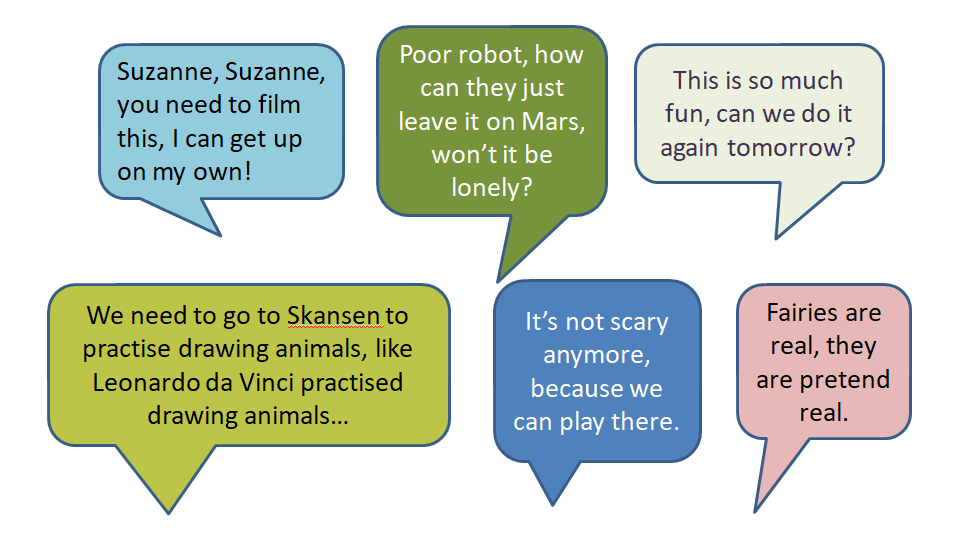

“You need to film me!” “Poor Robot!” “So much fun!”

The children know what my role is, I am there to take care of them and facilitate their learning. They know why I take photos and films, and write notes, they sometimes do this themselves. They frequently instruct me on what I should be filming or taking photographs of so that they can remember something important, or celebrate a milestone. They know that I am learning from them by observing their play, so that the activities I provide are meaningful.

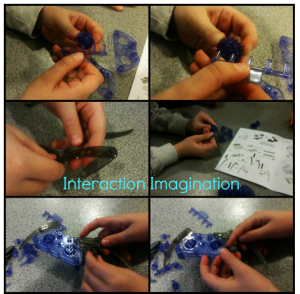

Building a robot to see if it had a heart or a brain… as the children said this is where feelings are felt.

They know that they can talk to me about anything (like robots being left on Mars) and that there will be space not only to dialogue together about this, but also time to play through the emotions triggered by it, and access to information to find out whether robots do feel lonely.

They also know they can impact how and where we learn. I did not at all want to travel the long journey by train and boat to the open air museum just because one child had not got splashed last time. But with the power of a “Thinking Pause” the children argued their case, linking it to the project we were exploring. Two days later we were on the other side of Stockholm drawing rainbow lorikeets.

Play is not just running around, or role-play: it is the brain’s way of adapting to a complex world, and that feels good so we keep on learning, as my neuroscientist husband tells me. So autonomy over learning, individually and as a community, is a form of play for children. It is not handing the power to the children, it is empowering the children to make informed decisions, and to know of their rights and responsibilities. Play is a space for that… children have the right to play, but equally they have the responsibility to play fair, otherwise they run the risk of no-one wanting to play with them.

“Like Leonardo!” “It’s not scary!” “Fairies are real!”

Sometimes the paper was eliminated because

painting was not the primary aim, but being allowed

to clean a floor like Cinderella was the play of the day

With art we have played with paint, paper – with all sorts of media, to fully understand how they work, how they communicate the children’s thinking and to allow the children to explore multiplicity. So many of the art activities have resulted in the children wanting to do it again and again. Every time when I ask my five, turning six, year olds if there is any activity they would like to do again before they leave to start school, 90% of the time it is an open art activity, and most often the one where they have big paper on the floor, stripped to their underwear and they paint with their whole bodies – the energy is amazing!

Play has been the way we have dealt with fear. Many five year olds go round with the fear of the dark (younger and older children too) so we took things that lit up into a dark room to play and explore. There was a lot of screaming the first few times, and some left the room, but after a few weeks of playing there and seeing the photographs the fear subsided for every-one. This was “risky play”, that tummy tickling excitement of learning to be brave, safely.

When I was told by a child that fairies were “pretend real”, I gained a deeper understanding of play. Play is real, pretend real. It is the space and time children can safely make sense of the world. Play is the optimal way to understand the world, that is why the brain makes it feel good for all ages so we keep on learning.

Being shown the fairy that had just been discovered in the forest. The International Fairy Tea Party proved to be a yearly celebration that allowed us to make many transdisciplinary discoveries through play and imagination.

Suzanne Axelsson lives in Stockholm and has worked with preschool children for thirty years. She now also teaches part-time at Stockholm University and gives workshops and presentations on early childhood education all over the world.