by Charlotte Bowes

I have been fortunate enough to spend the last 7 years working in Primary 1 & navigating a journey from traditional1 to play-based practice (with lots still to learn).

At each step along the way, every change made within the children’s environment – spaces, interactions & experiences2 – has been rooted in research & documented in my ‘Play Policy’, to share with children, families & staff.

The interactive working document is co-created with the children & scaffolded around Whitebread & Basilio’s 4 components of self-regulation3:

- emotional warmth & security

- feelings of control

- articulation of learning

- cognitive challenge

Play pieces

Each chapter is populated with ‘Play Pieces’ that explain the rationale behind our day-to-day choices; from in the moment planning4 to visible learning disposition dinosaurs5; from our RRS Class Charter6 to Helicopter Stories7.

Each ‘Play Piece’ has a symbol to make the ‘Policy’ visible within our classroom, supporting the children to confidently describe how it affects their day of play. There’s also accompanying reflection questions for staff to evaluate the provision & a ‘Parent/carer/guardian Poster’ so that families can continue their child’s learning at home.

When considering the initial content, before I had my own experience to rely upon, I took inspiration from international examples of high quality practice, starting with the Singapore Kindergarten Framework’s aims of producing joyful, curious & gracious learners8 (which forms our ‘Policy’ vision).

The Child at the Centre

Considering 5 high quality curricular & pedagogical models from around the world9 – High/Scope, Reggio Emilia, Te Whãriki, Experiential Education & the Swedish Curriculum – several commonalities are found, with one particular theme standing out: a rights-centered focus on children as individuals, & care/love within the curriculum10.

Considering 5 high quality curricular & pedagogical models from around the world9 – High/Scope, Reggio Emilia, Te Whãriki, Experiential Education & the Swedish Curriculum – several commonalities are found, with one particular theme standing out: a rights-centered focus on children as individuals, & care/love within the curriculum10.

In New Zealand they call it Mana Whenua, in Scotland we call it Being Me2.

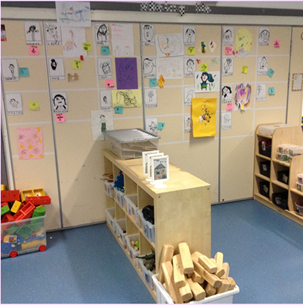

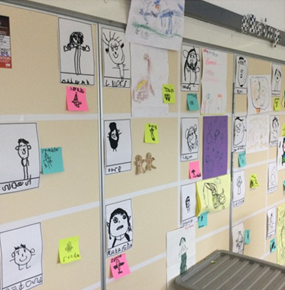

It is this sense of belonging that I want my new class to feel from the very first moment they enter their new environment, which is why I created the Being Me Wall: a display that evolved over the course of the year in P1, continued with the children into P2 & is now waiting for their return in August – to P3, a new classroom & a new teacher.

As such, the Being Me Wall ‘Play Piece’ supports the children’s “change process”11 as it progresses through every chapter of the ‘Play Policy’, & (as just one small element of our transition programme) has enabled us to create a successful transition experience, from Nursery to Primary 1.12

Emotional warmth and security

The 1st use of our Being Me Wall is to welcome the children into their new environment, by including:

- family photos as a source of comfort & familiarity for each child, & as a support in learning more about the children, for staff.

- meaningful additions discovered through our transition conversations, visits & activities – for example, pictures of their interests or photos of them having fun over the summer (taken from our virtual transition classroom) – to spark conversation & build relationships.

Feelings of control

The Being Me Wall is divided such that every child has a permanent, individual space to call their own: the display changes on a near daily basis as the class fill their sections in any way they choose.

It also functions as an integral part of our approach to observation, displaying:

- our in the moment planning post-its which, based upon the team’s daily play observations, contain the children’s individual targets & the adults’ next steps in preparing the environment to support them.

- the children’s ideas & suggestions (often scribed), so they truly understand that their thoughts are heard, valued & acted upon

Articulation of learning

As a dynamic feature of our environment, the use of the Being Me Wall acts as a focal point for conversation within the class, discussing:

- our ‘Magic Moment’ play observations which are pinned up to celebrate & share the children’s successes & achievements (they love to show every visitor!).

- evidence from our direct teaching inputs, chosen by the children.

Cognitive Challenge

Used across the year, in this way, the Being Me Wall allows us to demonstrate the children’s progress by documenting the:

Used across the year, in this way, the Being Me Wall allows us to demonstrate the children’s progress by documenting the:

- evolution in their black line self-portraits & name writing, which are repeated termly & displayed one on top of the other.

- development of their play across the year, from August to July:

– by interest e.g. the difference in how they roleplay shops,

– by skill e.g. the difference in how they cut paper,

– by resource e.g the difference in how they use the same bricks.

Inspired by my P1 Being Me Wall our Nursery team have now developed a similar approach within their environment, adding further consistency, sense of belonging and support for transition13, across our school community.

In terms of next steps, I’m in the middle of making an interactive copy of our Being Me Wall for families to use, in the hopes of further strengthening our home-school relationships: led by the children & celebrating all things play! #SharingtheAmbition

References

References

- Fisher, K. R., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Michnick Golinkoff, R. & Glick Gryfe, S., 2008. Conceptual Split? Parents’ and Experts’ Perceptions of Play in the 21st Century. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29(1), pp. 305-316.

- The Scottish Government, 2020. Realising the Ambition, Livingston: Education Scotland.

- Whitebread, D., & Basilio, M. (2012). The emergence and early development of self-regulation in young children. Profesorado: Journal of Curriculum and Teacher Education, 15-34.

- Ephgrave, A. (2018). Planning in the Moment with Young Children: A Practical Guide for Early Years Practitioners and Parents. Abbington-on-Thames: Routledge.

- Hattie, J. (2011). Visible Learning for Teachers (1st ed.). Abington: Routledge.

- (2022). RRSA: What is a Rights Respecting School? Retrieved from UNICEF: https://www.unicef.org.uk/rights-respecting-schools/the-rrsa/what-is-a-rights-respecting-school/

- Helicopter Stories Lee, T. (2015). Princesses, Dragons and Helicopter Stories: Storytelling and story acting in the early years. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ministry of Education, Singapore. (2012). NURTURING EARLY LEARNERS: A Framework for a Kindergarten Curriculum in Singapore. Ministry of Education, Singapore.

- Laevers, F. (2005). The curriculum as means to raise the quality of early childhood education. Implications for policy. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 13(1), 17-29.

- Directorate for Education, OECD . (2004). Starting Strong: Curricula and Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education and Care. Paris: OECD .

- Fabian, H. (2006). Informing Transitions. In A.-W. Dunlop, & H. Fabian, Informing Transitions in the Early Years (pp. 3-20). New York City: McGraw-Hill Education.

- (2017). Starting Strong V: Transitions from Early Childhood Education and Care to Primary Education. OECD Publishing.

- Dockett, S., & Perry, B. (2005). ‘You Need to Know How to Play Safe’: children’s experiences of starting school. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 4-18.