We all know politicians use statistics to cover up the truth. John Swinney is brilliant at it. Within a minute of him starting to drone on about numbers, I’m ready to accept any old rubbish if only he’ll stop.

But this month the Herald (bless it!) published a series of articles on Additional Support needs in Scottish schools and I can’t ignore those stats any more. The Scottish government is currently selling us a load of nonsense and it mustn’t go on because it is damaging children.

I’ve therefore started this blog with a very big version of one of the Herald’s graphs because I want it to be as easy as possible to read the small print. It records increases in Additional Support Needs (ASNs) in Scottish schools between 2007 and 2024.

It’s an extremely alarming increase. ASNs went from roughly 5% in 2007 to just over 40.5% in 2024. That’s an increase of 700% and a really important news story. Indeed for the 40% of Scotland’s schoolchildren who have additional needs (and for their families) it’s a tragedy. Because while ASN has increased, the level of individual support in schools has decreased. Local councils can no longer afford support assistants.

And now the ‘good news’…

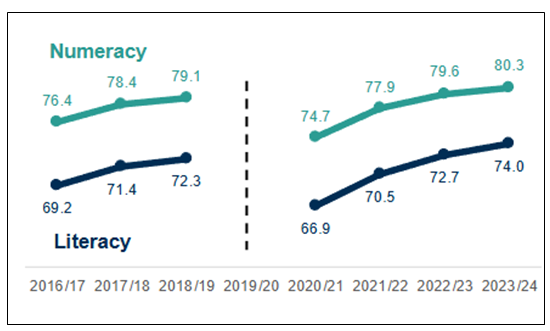

Mr Swinney would therefore prefer you to give your attention to the graphs on the left, which tell this month’s ‘good news story’. Ever since he was the Education Secretary who launched a drive to close the poverty-related attainment gap, primary children’s scores in literacy and numeracy have gone up! They’ve improved by roughly 15% for numeracy and 17.5% for literacy! Hooray! ***

Mr Swinney would therefore prefer you to give your attention to the graphs on the left, which tell this month’s ‘good news story’. Ever since he was the Education Secretary who launched a drive to close the poverty-related attainment gap, primary children’s scores in literacy and numeracy have gone up! They’ve improved by roughly 15% for numeracy and 17.5% for literacy! Hooray! ***

Actually, it would be strange if those scores hadn’t gone up. For the last seven years, there’s been relentless pressure on primary schools – from both national and local government – to improve literacy and numeracy results. It starts at P1, when they’re five years old. Some local authorities track children’s progress in these subjects from the minute the poor wee souls enter nursery.

Followed by the really bad news

Nevertheless, the poverty-related attainment gap is still growing year by year. The last administration threw £750 million pounds at it, followed by another £1 billion in the current Parliament. So it’s clear that focusing on the three Rs from an early age is not helping close the gap. In 2018, I wrote a paper explaining why it wouldn’t and Upstart sent to it Mr Swinney. I don’t suppose he read it.

Nevertheless, the poverty-related attainment gap is still growing year by year. The last administration threw £750 million pounds at it, followed by another £1 billion in the current Parliament. So it’s clear that focusing on the three Rs from an early age is not helping close the gap. In 2018, I wrote a paper explaining why it wouldn’t and Upstart sent to it Mr Swinney. I don’t suppose he read it.

Since the 25% of Scotland’s children who live in poverty tend to be the children with the most pressing additional support needs, God knows the long-term damage this obsession with an early start on formal education is doing to them.

Over the last fifteen years, Scotland has also seen horrific increases in mental health problems among children and young people (currently a hundred referrals a day, according to STV News) and there have been notable increases in behavioural problems, especially in primary schools (see this government report).

All this adds up to a tremendous amount of misery among Scottish children, particularly those from the poorest homes. The old mantra of ‘education, education, education’ simply isn’t working.

Development, development, development

The reason this makes me so angry is that people have been predicting these problems for a long time. In 2007 (the year they started recording ASN in the Very Big Graph above) I signed a press letter from 112 experts in various aspects of child well-being. It was about changes in our culture that are damaging for children, and began with the following words:

The four main cultural changes cited in that letter were:

The four main cultural changes cited in that letter were:

- the decline of active outdoor play

- increasingly screen-based lifestyles

- the commercialisation of childhood

- a hyper-competitive schooling system, starting at a very early age.

It’s message was that 21st century policy-makers should concentrate on supporting children’s overall development, especially in the early years, when they develop the underpinning capacities on which lifelong learning and mental health depend. Nobody in government or educational circles took a blind bit of notice, so in 2016 I joined other experts in child development to launch the Upstart Scotland campaign.

We’re campaigning for a rights-focused, relationship-centred, play-based kindergarten stage for children between three and seven years old. It isn’t the answer to all Scotland’s educational woes, but it could help address the terrifying rise in ASN, behavioural difficulties and mental health problems. There’s plenty of evidence to support our claim and we made a three minute film to sum up the arguments.

Unless politicians stop obsessing about irrelevant data and start taking notice, things can only get worse.

*** P.S. After publication, I was contacted by someone who knows infinitely more about statistics than me, with the following message: “The one thing missing from it is a key for the “gap”/time-trend graph for literacy and numeracy scores over recent years, so that the reader is not able to discern what the two lines represent. I presume they are the scores for two categories of students, categorized by a measure of socio-economic status (perhaps the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation by household address? or parental education level achieved?) If you could issue a short “Corrigendum” explaining what the two lines mean, and that the higher the score, the better the attainment, that would be great!”

Sue Palmer is a former primary head teacher, literacy specialist and author. Her best known book, Toxic Childhood: how the modern world is damaging our children and what we can do about it, was published by Orion (2006, second ed.2015)