Sue Palmer

When builders start work on a building, they begin – of course – with the foundations. Unless it’s built on a secure base, any construction will be, at very the least, wobbly.

So you’d think that, before drawing up plans to ‘build back better’ in post-COVID Scotland, policy-makers in the Scottish education department would have at least checked out the state of the system’s current foundations. They’ve certainly received plenty of messages over the last five years, suggesting that all is not well in Curriculum for Education‘s Early Level.

What’s wrong with Early Level?

Upstart sent John Swinney our first communication on the subject in November 2015 (and also published it as a blog). Since then, we’ve written many more letters, emails, papers, submissions and blogs. We even sent every single MSP a copy of our recent book, Play Is The Way, in which we argue that a ‘straight-through Early Level’ (or ‘kindergarten stage’) would be the best way to ensure that all Scottish children have time to develop the physical, social, emotional and cognitive capacities that will help them thrive, not only in education, but throughout their lives.

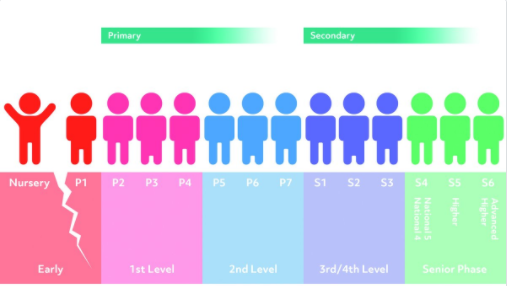

At present, the Early Level is split in two. This means there’s an abrupt transition from nursery to school when children are four or five. Having settled into a nursery setting only a year or so earlier, these wee ones have to readjust to a very different educational ethos: different building; different adult carers (who are trained in primary teaching rather than early learning; changed adult:child ratios (which lurch from 1:8 to 1:20), and a ‘schoolified’ emphasis on literacy/numeracy acquisition, rather than learning through play.

From a developmental perspective, this massive change is highly inappropriate at the age of four or five. It’s roughly half-way through a very critical stage for development (‘early childhood’) which is defined by the United Nations as birth to eight. Indeed, for many children – especially those from low income homes – there’s a good chance that such a premature change of educational ethos will cause social and emotional damage, which will then impact on their long-term educational chances and/or mental health.

From a developmental perspective, this massive change is highly inappropriate at the age of four or five. It’s roughly half-way through a very critical stage for development (‘early childhood’) which is defined by the United Nations as birth to eight. Indeed, for many children – especially those from low income homes – there’s a good chance that such a premature change of educational ethos will cause social and emotional damage, which will then impact on their long-term educational chances and/or mental health.

It’s therefore not surprising that research now shows Primary 1 pupils to have been particularly adversely affected by the COVID lockdowns, as of course have children from low income homes.

Building back better?

I therefore had high hopes that Education Scotland’s recent document about the COVID crisis – What Scotland Learned: building back better – would start with a long hard look at Early Level. And was horrified to find that the early years of education are scarcely mentioned.

I therefore had high hopes that Education Scotland’s recent document about the COVID crisis – What Scotland Learned: building back better – would start with a long hard look at Early Level. And was horrified to find that the early years of education are scarcely mentioned.

I was similarly horrified by the Scottish Government’s National Improvement Framework [NIF] and Improvement Plan for 2021 (and the Equity Audit on which it’s based) – again only the merest mention of early years. In the 2015 blog mentioned earlier, Upstart argued that the Framework’s lack of attention to early child development was more likely to widen the poverty-related attainment gap. Research in 2020 showed that, even before COVID, the attainment gap was yawning as wide as ever, so you might have expected the authors of a 2021 version of NIF to reconsider their criteria … but no – it’s mainly a tweaking exercise.

This blind spot about Early Level isn’t confined to the Government. Most folk in the higher echelons of Scottish education seem blissfully unaware of its significance. For instance, in November 2020, I attended a high-profile online conference (organised by the GTC and Scotland’s Futures Forum) to discuss ‘building back better’. The eminent presenter and his (often pretty eminent) questioners discussed many possible tweaks to CfE but early years didn’t get a mention, even though the Futures Forum published a document earlier in the year recommending a kindergarten stage for three- to eight-year-olds.

Building back downwards

To return to the building analogy, the foundations of a building are buried under the ground – out of sight and therefore generally out of mind. And young children who are developing the physical, social, emotional and cognitive foundations upon which their future educational success depends seem destined to remain similarly invisible to policy-makers. The people with the power just sit high up on the roof, wondering why the building is so wobbly…

It’s clear from all the documents and discussion that their plans for building back better revolve entirely around ‘school’ – starting with secondary school, then building downwards into primary school (and, as far as they’re concerned, Primary 1 is just the first year of school). They don’t even consider nursery because in policy-making terms, ‘nursery’ is synonymous with ‘childcare’ (which they don’t really consider as ‘education’ – merely an economic necessity so that parents can go out to work…).

So Early Level has never been properly recognised throughout the rest of the education system as a discrete developmental stage of CfE, requiring a very different educational ethos from ‘school’.

Development matters

This sort of top-down thinking wouldn’t work in the building industry and it hasn’t worked in education. Not least, of course, because children aren’t items of building material. They’re human beings, whose development requires careful nurturing, especially in the early stages. This is why, 200 years ago, Friedrich Froebel didn’t use the word ‘school’ when he set up a system of educational provision for three- to seven-year-olds. Instead he coined the term ‘kindergarten’ (‘children’s garden’) to describe principled, relationship-centred, play-based pedagogy for this age group. And that’s why Upstart argues for a dedicated, coherent ‘kindergarten stage’, rather than an Early Level that’s widely misunderstood and dismissed as irrelevant.

There are now very many people working in early childhood education, including P1 and 2, who do understand the significance of early child development and are trying very hard to build back better from the bottom up. But they need support from the policy-makers and managers throughout the system – without it, the top-down pressure to reach inappropriate age-related standards in literacy and numeracy means it’s impossible to provide genuine play-based pedagogy.

There are now very many people working in early childhood education, including P1 and 2, who do understand the significance of early child development and are trying very hard to build back better from the bottom up. But they need support from the policy-makers and managers throughout the system – without it, the top-down pressure to reach inappropriate age-related standards in literacy and numeracy means it’s impossible to provide genuine play-based pedagogy.

Until there is universal recognition of the need for developmentally-appropriate provision for the under-sevens, Scotland’s educational edifice will continue to wobble. But far worse than that, more generations of children will suffer lasting damage to their mental health and well-being because their early developmental needs have been not met by the educational system.

To build back better in education, Scotland must recognise that the way to build safely is upwards. And to recognise and celebrate the expertise of early years professionals who help children develop secure foundations.

Excellent article if ever there was a time to strip back to the framework of the educational house and rebuild properly this would be the time .

The current set up is not catering for every child and what they need to develop inthe right way.