Part Two of a guest blog by Mine Conkbayir

In Part One of this blog I discussed the detrimental impact of early testing and ‘behaviour management’ policies and practices on children’s mental health. In Part Two, I will explore the foundation that holds all this together: self-regulation (SR). Sadly, many teachers don’t fully understand the meaning of this term.

The key to a fulfilling and successful life, is one’s ability to manage one’s own emotional responses and consequent behaviour; to know how to control those big, overwhelming feelings such as anger or fear in order to get on with the serious business of play, exploration and learning. In short, it means being able to choose how we respond. This capacity, along with other key attributes, is known as self-regulation (SR). So, what else does this often-misunderstood skill involve? Broadly speaking it includes these 10 attributes:

The key to a fulfilling and successful life, is one’s ability to manage one’s own emotional responses and consequent behaviour; to know how to control those big, overwhelming feelings such as anger or fear in order to get on with the serious business of play, exploration and learning. In short, it means being able to choose how we respond. This capacity, along with other key attributes, is known as self-regulation (SR). So, what else does this often-misunderstood skill involve? Broadly speaking it includes these 10 attributes:

- Controlling own feelings and behaviours

- Self-soothing/bouncing back from upset

- Being able to curb impulsive behaviours

- Being able to concentrate on a task

- Being able to ignore distractions

- Behaving in ways that are pro-social (like getting along with others)

- Planning

- Thinking before acting

- Delaying gratification

- Persisting in the face of difficulty.

Self-regulation is not compliance!

There are many, varied definitions of SR but my personal favourite is this concise definition by the eminent neuroscientist, Dr Dan Siegel (2017), as I think it is a view that sounds familiar to many of us. He says:

In my office, I describe self-regulation as ‘’The amount of stress I can take without FREAKING OUT at someone’’.

Research continually shows that a child’s ability to self-regulate at three-years-old is a better indicator of school success than IQ…

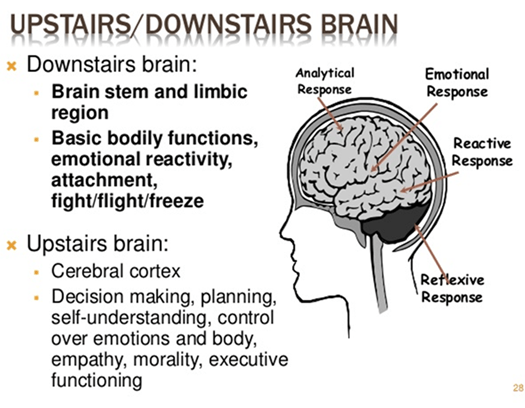

This is where the ‘’upstairs’’ and ‘’downstairs brain’’ come in

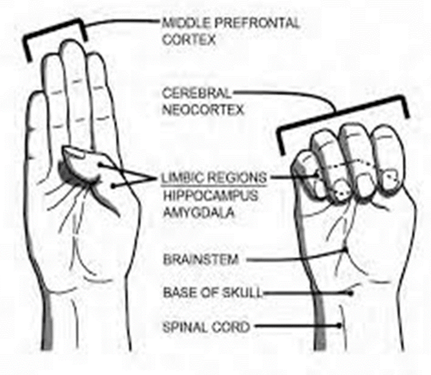

You may be wondering why I emphasise mental health over academic proficiency – after all, we need to be able to count and to read in order to get by in life. The answer is simple and can be found in the work of Daniel Siegel, specifically, ‘’the brain in the palm of the hand’’.

Early brain development is a highly precarious process and this is partly because the brain is such a highly receptive organ. This of course can be a positive thing when it comes to the teaching and learning process, given that synaptic connectivity increases as a result of engagement with the environment and the people and experiences within it.

However, when an infant’s or child’s environment is not a happy, secure and enriching one – and is instead filled with harsh treatment and responses, poor care, abuse or neglect – synaptic connectivity, brain growth and consequent behaviour develop in line with these negative experiences. The brain of a young child develops in reaction to the way it has been stimulated.

However, when an infant’s or child’s environment is not a happy, secure and enriching one – and is instead filled with harsh treatment and responses, poor care, abuse or neglect – synaptic connectivity, brain growth and consequent behaviour develop in line with these negative experiences. The brain of a young child develops in reaction to the way it has been stimulated.

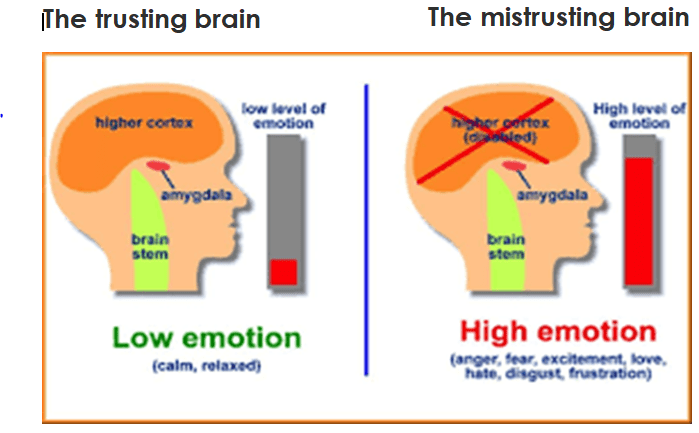

Due to the over-stimulation of brain regions like the amygdala (the brain’s ‘panic button’), brainstem (home to many of the control centres for vital body functions) and the stress hormone, cortisol, the child’s ability to cope under stressful situations is greatly diminished.

The diagram below shows that a child who (for example) has not experienced any adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), is able to operate from their upstairs brain and use those executive functioning skills necessary for academic success. However, those children who have experienced ACEs are not able to access their upstairs brain, functioning from their emotionally reactive downstairs brain.

Chronic, toxic stressors (like ACEs and trauma) trigger long-term changes in brain structure and function, including shrinkage of the hippocampus (regulates memories and emotions), a decrease in the volume of grey matter (responsible for executive functions like delaying gratification, curbing impulsive behaviour, managing overwhelming feelings, concentrating and problem-solving).

Critically, what results is reduced connectivity between the emotionally reactive, downstairs brain (home to the brain’s ‘panic button’ – the amygdala) and the cortical, upstairs brain (home to the prefrontal cortex [PFC] – where our executive functions reside). This reduced connectivity happens when a child feels threatened, distressed, humiliated, embarrassed, scared or angry and they ‘’flip their lid’’, because the upstairs brain has lost control of the downstairs brain (as the amygdala – that panic button, has been activated). This ‘lid-flipping’ is depicted in the ‘’brain in the palm of the hand’’ below:

This of course happens in milliseconds and this is often when a child’s behaviour is labelled as ‘’challenging’’ and they are swiftly reprimanded. What they actually need is adult support (co-regulation) to return to a safe psychological state – to help put that lid back down, so that they are able to learn.

I mentioned the PFC, a critical region in the upstairs brain. It is also the most evolved brain region and one which we demand far too much of children without putting in any staff training or support for children, to nurture its development. However, it is also the brain region that is most sensitive to the detrimental effects of stress exposure (Arnsten, 2009).

Moreover, it takes at least 26 years for the PFC to fully develop! When we reflect on this with regard to what is demanded of very young children and the impact on their mental health, we know that things must change.

Until UK policy-makers and leadership teams transform their requirements in early childhood education (3-7), nothing can change on a large and consistent enough scale. We need policies, frameworks for learning and any measurements of a school’s impact to have embedded children’s psychological well-being with greater parental engagement to provide a seamless learning journey between the home and the setting.

In the meantime, every practitioner who feels their provision is at odds with children’s well being owes it to those children, to make a stand. This might mean a long overdue conversation with your setting’s management team, it might mean revising your behaviour, key person or Health and Wellbeing (Personal and Social Education) policies and practices or standing up to local authority advisers. It may well require you to do all three!

Mine Conkbayir

To sign up to Mine’s new self-regulation e-learning programme, contact Mine at mine@mineconkbayir.co.uk

Mine’s first-ever conference takes place on 4 February 2019. Details can be found at: https://www.butterflyprint.co.uk/product/conference-the-neuroscience-of-early-intervention/