by Sue Palmer

Scotland has been making huge progress in early years practice over the last few years. More and more P1 teachers have started following the developmentally-informed guidance in Realising the Ambition – lots of P2 teachers too. And, in nurseries at least, there have been great leaps forward in terms of outdoor play and learning, along with far more opportunities for many children to spend time in nature. Given all this good news, it presumably seems like nit-picking to the Scottish government when Upstart continues to bang on about the P1 assessments in literacy and numeracy.

Scotland has been making huge progress in early years practice over the last few years. More and more P1 teachers have started following the developmentally-informed guidance in Realising the Ambition – lots of P2 teachers too. And, in nurseries at least, there have been great leaps forward in terms of outdoor play and learning, along with far more opportunities for many children to spend time in nature. Given all this good news, it presumably seems like nit-picking to the Scottish government when Upstart continues to bang on about the P1 assessments in literacy and numeracy.

But it isn’t nit-picking. In terms of getting early childhood care and education right, the P1 tests undermine all the progress described above. So, as we move into another year of Covid-19, here are two reasons they must be scrapped:

- Reason 1: The P1 tests may only happen once a year but – along with the associated benchmarks for attainment – they adversely affect pedagogical practice all year round. They also perpetuate false expectations of five-year-old children that can lead to social and emotional problems as time goes on.

- Reason 2: Even before the pandemic, Scotland was struggling to cope with steadily increasing mental health problems among children and young people. Most of these problems have their roots in adverse childhood experiences, particularly during early childhood (birth to eight). After two years of Covid-19 – and with who know how much longer to go – it’s urgent that early years care and education focuses on health and well-being, rather than premature academic attainment.

Play-based pedagogy versus age-related standards

The adverse effects on early years practice mentioned in Reason 1 relate to the difference between a play-based, developmental approach (as described in Realising the Ambition and adopted in kindergartens worldwide) and the age-related, standards-driven approach commonly associated with ‘school’ (see figure 1).

There’s international agreement that, during early childhood, the focus should be on children’s holistic development (physical, social, emotional and cognitive) with the aim of building ‘a broad and solid foundation for lifelong learning and wellbeing’.

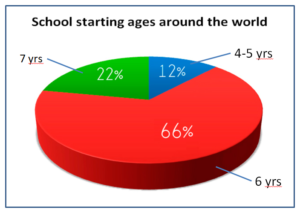

Most of the world’s children wouldn’t even be in school at five years old (see Figure 2, below) so no one would dream of assessing their literacy and numeracy skills. But, thanks to history, Scottish children start school extraordinarily early. And, thanks to widespread ignorance in UK countries about early child development, Scottish policy-makers chose to introduce national standardised assessment of the three Rs in P1.

And they’ve stuck with that decision despite fierce opposition from organisations such as the EIS and Children in Scotland (both of which know quite a bit about child development), a parliamentary vote in 2019 to scrap the P1 tests and advice last year from experts at the OECD, which has since published research about the developmental needs of five-year-olds (see this month’s Upstart newsletter).

A cultural dilemma

Scotland’s cultural ignorance about child development is almost certainly linked to our early school starting age. Scottish children have been starting compulsory education at five for 150 years, so we assume that’s the age they should start learning the three Rs. The authors of Curriculum for Excellence tried to change things by creating an ‘Early Level’, covering nursery and P1, which takes a developmental approach until children are six.

But cultural assumptions die hard – P1 children are in school, so in Scottish minds they should be treated as schoolchildren. This was clearly the view of politicians and civil servants when they decided to introduce Scottish National Standardised Assessments in literacy and numeracy. To establish a baseline for children’s ongoing progress, the first tests were set in P1. And to give an indication of the sort of standards expected of P1 children they commissioned Early Level ‘benchmarks’ for attainment.

These benchmarks are entirely arbitrary – there is no reason whatsoever to expect five-year-old children to read, write or reckon to a particular standard. They are also aspirational in the extreme (some samples are shown on the right). And they bear very little resemblance to the Early Level as described in Curriculum for Excellence but a great deal to targets devised for English five-year-olds at around the time the SNSA was being dreamed up.

These benchmarks are entirely arbitrary – there is no reason whatsoever to expect five-year-old children to read, write or reckon to a particular standard. They are also aspirational in the extreme (some samples are shown on the right). And they bear very little resemblance to the Early Level as described in Curriculum for Excellence but a great deal to targets devised for English five-year-olds at around the time the SNSA was being dreamed up.

When the SNSAs were eventually introduced across Scotland in 2018, they were pounced on local authority bureaucrats, who generally know as little about child development as government policymakers but are very keen for their LA to do well in any sort of competition. They were therefore extremely interested in the SNSA results and have ever since put considerable pressure on schools to perform well against the age-related ‘benchmarks’.

In response to LA demands, senior managers in schools have passed this pressure down to P1 teachers who, in turn, have felt obliged to pass it down to five-year-old children by teaching them phonics, handwriting skills and number bonds, and sorting them into ability groups for reading and maths. The P1 tests may happen only once a year, but preparation for them goes on every day of every school term.

In response to LA demands, senior managers in schools have passed this pressure down to P1 teachers who, in turn, have felt obliged to pass it down to five-year-old children by teaching them phonics, handwriting skills and number bonds, and sorting them into ability groups for reading and maths. The P1 tests may happen only once a year, but preparation for them goes on every day of every school term.

Media coverage of education is as hopelessly stuck in the ‘early start’ cultural paradigm as educational policy, so the aspirational Scottish parents who read it also believe their five-year-olds should be cracking on with the three Rs, thus adding to the pressure on the P1 workforce – and, of course, the children.

The result is a dilemma for P1 teachers, who are being required to follow two completely incompatible approaches:

- On the one hand, Realising the Ambition tells them to adopt a pedagogical approach based on each individual child’s stage of development

- On the other, their LA paymasters expect them to teach literacy and numeracy skills based on age-related ‘standards’ to all children, regardless of developmental stage.

It’s a nasty dilemma because the last thing a sensitive practitioner wants to do is put many children off these important skills by pushing them to perform tasks for which they aren’t developmentally ‘ready’.

Early child development matters

Our society has become so obsessed with the importance of education that we’ve lost sight of the importance of childhood. From the moment of birth, children are primed by evolution to develop a vast range of skills and capacities naturally. Apart from obvious skills, such as walking and talking, most adults aren’t aware of all the physical, social, emotional and cognitive progress children are genetically programmed to make, so don’t see the need to give them plenty of ‘childhood time’ in which to make it.

Our society has become so obsessed with the importance of education that we’ve lost sight of the importance of childhood. From the moment of birth, children are primed by evolution to develop a vast range of skills and capacities naturally. Apart from obvious skills, such as walking and talking, most adults aren’t aware of all the physical, social, emotional and cognitive progress children are genetically programmed to make, so don’t see the need to give them plenty of ‘childhood time’ in which to make it.

In a supportive environment (such as that described as a ‘kindergarten ethos’ in the chart above) the vast majority of children should develop all the foundational skills that render them able and willing to engage in formal schooling between the ages of six and eight. But when adults sideline children’s developmental needs in accelerated pursuit of the three Rs, they set up problems for the future.

Some children switch off from learning because they simply can’t cope with the teacher’s expectations and see themselves as failures from the start. Others are able to comply with their teacher’s requests but their schoolwork is henceforth ‘extrinsically motivated’, rather than pursued (as nature primed them to pursue it) for the joy of acquiring new skills and knowledge. And children are also effectively being trained to ‘be good for the teacher’, rather than developing the hugely important capacity to regulate their own behaviour.

Research-based evidence shows that this sort of neglect (and indeed sometimes disruption) of holistic development at such a critical stage can make children more vulnerable to social, emotional and mental health problems in future years.

On the other hand, there are two recognised ‘protective factors’ for children’s long-term mental health and well-being:

- The first is is caring, non-judgmental support from the adults in their lives, which helps develop self-regulation skills and executive function.

- The second is time and freedom to learn through play (especially adventurous play outdoors) which, through developing their capacity to cope with anxiety, enhances emotional resilience and a sense of personal agency.

This brings me to the second reason why ‘Play Not Tests for P1’ matters now more than ever. Scotland already has a horrifying mental health crisis among children and young people, which is set to become even more horrifying thanks to the Covid pandemic. Today’s five-year-olds have lived half their lives in a world of constant adult anxiety. Many have also missed out on fundamental everyday experiences vital for healthy development and long-term well-being. And, particularly for the most disadvantaged children, the pandemic has hugely increased the incidence of ‘adverse childhood experiences’, such as neglect, violence and bereavement.

This brings me to the second reason why ‘Play Not Tests for P1’ matters now more than ever. Scotland already has a horrifying mental health crisis among children and young people, which is set to become even more horrifying thanks to the Covid pandemic. Today’s five-year-olds have lived half their lives in a world of constant adult anxiety. Many have also missed out on fundamental everyday experiences vital for healthy development and long-term well-being. And, particularly for the most disadvantaged children, the pandemic has hugely increased the incidence of ‘adverse childhood experiences’, such as neglect, violence and bereavement.

The last thing this generation of five-year-olds needs is standardised assessment that not only skews all classroom practice in the direction of inappropriately formal learning, but also works directly against the two protective factors for mental well-being described above. By requiring that children should be judged against arbitrary aspirational standards, the P1 test adversely affects the teacher-child relationship and actually creates anxiety in everyone concerned.

Scotland’s children need time and support to recover from the pandemic. The support our five-year-olds need is love and play – not tests.

See also:

Upstart’s 2019 short film about the P1 tests –Play is a Serious Business.

Self-regulation: what you need to know by Dr Mine Conkbayir