“The unreliability of the assessments, combined with the unreliability of five-year-olds, means these assessments are almost completely useless as guides to the achievement and needs of five-year-olds.”

That’s how Professor Dylan Wiliams – one of the world’s foremost experts in formative assessment – explained his opposition to Scotland’s use of standardised assessment (SNSA) in Primary 1.

Over recent weeks, discussion of the P1 tests by the Parliamentary Education Committee has covered the statistical reliability of SNSA at length but not, so far, the reliability of five-year-olds. And five-year-olds are, bless them, pretty unreliable.

I mean, would you entrust a five-year-old with a secret? Or expect them successfully to repeat a simple domestic task that you painstakingly explained a week ago? If you were inadvertently separated from a five-year-old in a crowded shopping centre, would you feel confident that they’d follow your well-drilled safety instructions?

I mean, would you entrust a five-year-old with a secret? Or expect them successfully to repeat a simple domestic task that you painstakingly explained a week ago? If you were inadvertently separated from a five-year-old in a crowded shopping centre, would you feel confident that they’d follow your well-drilled safety instructions?

Or, if you’re a teacher, try this simple numeracy test: In a group of twenty five-year-olds, how many might answer the question ‘3+7’ correctly? And how many would come up with the same answer tomorrow?

Executive function, self-regulation and standards

Even though most five-year-olds have already made remarkable progress in physical control, spoken language and social skills, they’ve a long way to go before they’re emotionally and cognitively ‘reliable’.

What’s more, in any group of five-year-olds, there’s enormous variation between developmental levels.

Human development is profoundly influenced by both nature (elements of an individual’s genetic makeup) and nurture (the emotional, social and cultural experiences available to the child so far).

So, as Professor Wiliams succinctly explained, assessing this highly ‘unreliable’ age-group against a collection of educational ‘standards’ is a waste of everyone’s time.

Time, nurture and culture

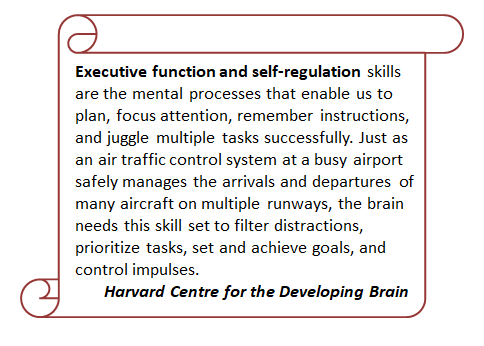

In terms of their long-term educational success (as well as long-term well-being), what five-year-olds really need is time to develop their executive functions and self-regulation skills (see scroll above). For this, they depend upon adults to provide a nurturing environment – i.e. supportive emotional, social and cultural experiences – in which to practise focusing their attention, remembering instructions, and juggling multiple tasks.

In terms of their long-term educational success (as well as long-term well-being), what five-year-olds really need is time to develop their executive functions and self-regulation skills (see scroll above). For this, they depend upon adults to provide a nurturing environment – i.e. supportive emotional, social and cultural experiences – in which to practise focusing their attention, remembering instructions, and juggling multiple tasks.

Unfortunately, when adults are confronted with educational standards, they usually succumb to the temptation to ‘cut to the chase’ – which in this case means direct teaching of specific cognitive skills. Scotland’s introduction of literacy and numeracy SNSAs now focuses P1 teachers’ attention on doing just that.

But successful acquisition of specific cognitive skills depends on well-developed executive functions and self-regulation. And for this, first and foremost, children need effective emotional support. It’s no coincidence that the word ‘emotion’ is related to ‘motion’ and ‘motivation’ – during early childhood, emotion motivates all behaviour and learning.

Emotions, motion and motivation

From the day children are born, primary emotions like joy, fear, anger and surprise drive their behaviour and learning. By five years old, they may have begun behaving in more adult-like ways, but they’re still very easily distracted when emotionally excited. (Indeed, even the most self-regulated adult can find it difficult to ‘plan, focus attention, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks successfully’ when gripped by great joy, anger or fear.)

So, to help five-year-olds develop self-regulation, the adults who care for them must provide an emotionally supportive environment. And this is, of course, particularly important for children from homes where, for whatever reason, positive emotional support was lacking in the past.

So, to help five-year-olds develop self-regulation, the adults who care for them must provide an emotionally supportive environment. And this is, of course, particularly important for children from homes where, for whatever reason, positive emotional support was lacking in the past.

This is why Upstart Scotland campaigns for a rights-focused, relationship-centred, play-based kindergarten stage for children between three and seven years of age. Children in this age-range are motivated to learn by consistent, non-judgemental, interactive support on behalf of their adult carers PLUS plenty of opportunities for active, self-directed play (as often as possible outdoors) with other children.

Biology comes before culture

Indeed, this is the sort of emotionally supportive environment that lucky human children have enjoyed for countless millennia. Thanks to evolutionary biology, the powerful combination of adult care and childhood play has enabled each generation of homo sapiens to develop not only self-regulation skills, but creativity, problem-solving skills, emotional resilience, social and communication skills and a host of other capacities that help human beings survive and thrive, including all-round physical and mental health.

Indeed, this is the sort of emotionally supportive environment that lucky human children have enjoyed for countless millennia. Thanks to evolutionary biology, the powerful combination of adult care and childhood play has enabled each generation of homo sapiens to develop not only self-regulation skills, but creativity, problem-solving skills, emotional resilience, social and communication skills and a host of other capacities that help human beings survive and thrive, including all-round physical and mental health.

When the spread of literacy made formal schooling essential, cultures worldwide chose seven as the starting age. And when the spread of democracy led to universal state education, most countries started it at seven or six (giving a year for children to settle in). Only a small handful (including Scotland) chose five.

There’s no reason (other than perverse national culture) for Scottish schools to begin the explicit teaching of specific literacy and numeracy skills when children are five. Some five-year-olds are motivated to read, write and/or reckon (and should, of course, be supported and encouraged) but others haven’t the foggiest idea what it’s all about. Activities like art, drama, music, singing, storytime, explorations and experiments (along with lots of exposure to books, letters and numbers), are the best ways to motivate and prepare all children for literacy and numeracy.

There’s no reason (other than perverse national culture) for Scottish schools to begin the explicit teaching of specific literacy and numeracy skills when children are five. Some five-year-olds are motivated to read, write and/or reckon (and should, of course, be supported and encouraged) but others haven’t the foggiest idea what it’s all about. Activities like art, drama, music, singing, storytime, explorations and experiments (along with lots of exposure to books, letters and numbers), are the best ways to motivate and prepare all children for literacy and numeracy.

On the other hand, pressing young children to acquire specific literacy and numeracy skills before they see the point is likely to backfire. While most of them can probably be trained to press buttons in response to tablet-based tests of literacy and numeracy, it will be at the expense of other important elements of their physical, social, emotional and cognitive development.

The importance of being five

So… what is the importance of being five?

It’s just that … being five. Gloriously, unreliably, unapologetically five.

If we give our five-year-olds a developmentally-appropriate educational environment, they’ll have the time, space and support to play, run, jump, sing, listen to stories, create, build, explore, experiment, learn, develop … and eventually enjoy the importance of being six.

As the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child says, ‘Early childhood education and care [0-8 years] is more than a preparation for primary school. It aims at the holistic development of a child’s social, emotional, cognitive and physical needs in order to build a solid and broad foundation for lifelong learning and well-being.’

Sue Palmer, Chair of Upstart Scotland

P.S. Of course, there must be a point at which educational standards kick in and we start explicitly teaching literacy and numeracy. Ancient wisdom, developmental psychology, modern neuroscience and – wonder of wonders! – the World Economic Forum now all agree that it’s around the age of seven (but good on the UNCRC for erring on the side of caution and going for eight!).

So very true. The importance of developing speech, language and interaction skills as a foundation for educational attainment cannot be overemphasized.

Nurturing a child and preparing them with the skills for learning has been studied and is the single factor that separates future life chances

So very true. The importance of developing speech, language and interaction skills as a foundation for educational attainment cannot be overemphasized.

Nurturing a child and preparing them with the skills for learning has been studied and is the single factor that separates future life chances