I’ve spent the day listening to coverage of the secondary exam fiasco in England. And feeling extremely proud of the Scottish government. Thank goodness they immediately recognised the inanity of prioritising a statistically-driven ‘system’ over the needs of young human beings who are already traumatised by five months of COVID-19 culture change.

How could any country that truly believes in social justice support a system which downgrades the efforts of students from schools in disadvantaged areas while bumping up results in the private sector? Yet, at time of writing, the Westminster government is doing just that.

Our government’s refusal to do so is further evidence that Scotland – in good old Scottish fashion – has colonised the educational high ground.

Has Scotland started looking north?

I say ‘further evidence’ because the last Upstart blog described the massive difference between Scotland’s current approach to early childhood care and education (ECEC) and the dreadful state of affairs down south. A huge gulf is opening between the two countries’ approach to ECEC … and I’m so grateful to be on the Scottish side!

Ever since Upstart began campaigning for a kindergarten stage, back in 2015, we’ve described it as based on ‘the Nordic model’ because play-based pedagogy in the early years – especially outdoor play in natural surroundings – is increasingly recognised as the best way to promote lifelong learning and well-being.

In many ways, Scotland has far more in common with the Nordic countries than with England. So, rather than pursuing an Anglicised ‘schoolification’ of early childhood, we believe that relationship-centred, play-based, outdoors ECEC is an excellent way to address many of Scotland’s ingrained educational problems, including the poverty-related attainment gap (see Upstart’s FAQs and Play Not Tests document).

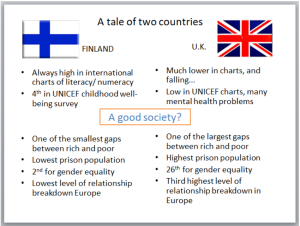

Not only do Nordic countries have far higher levels of childhood well-being than the UK, they also have a far less worrying gap between rich and poor. There are, of course, many reasons for these differences but I shall always treasure the words of a Finnish government minister in 2004:

‘It was not always like this,’ he said, ‘but thirty years ago we thought: “How do we get a good society?” And we said: “We must look after our little children.”‘

Trust versus control

Last week, I was asked (for an article in the National) how I’d reduce the poverty-related attainment gap. I replied that, since the gap is evident by the age of three, we should provide support for disadvantaged parents before and during the first three years of their children’s lives. And, since research shows that play-based pedagogy is the most effective type of ECEC, we should also update our universal services and introduce a relationship-centred, play-based kindergarten stage for the under-sevens.

Another interviewee for this National piece was Dr Suzanne Zeedyk. Asked the same question, she replied: ‘Addressing inequality in Scotland begins with creating trust. It sounds simple but it isn’t. Inequality drives distrust and division. That leaves people legitimately feeling that they are not heard and that they don’t matter, which stokes anxiety, anger and suspicion.’

In 2018, after my most recent visit to Finland, I wrote an Upstart blog entitled ‘A Tale of Two Systems’. It argued that Finnish politicians (and therefore the Finnish people) have chosen to trust teachers. Teachers therefore feel free to trust the children in their care to learn and prosper. The UK, however, is locked into a culture of centralised control.

In 2018, after my most recent visit to Finland, I wrote an Upstart blog entitled ‘A Tale of Two Systems’. It argued that Finnish politicians (and therefore the Finnish people) have chosen to trust teachers. Teachers therefore feel free to trust the children in their care to learn and prosper. The UK, however, is locked into a culture of centralised control.

If you trust little children to ‘learn with joy’ (as prescribed by the – very slim – Finnish preschool guidance for children under seven), that trust in the human spirit affects the whole of society. Why? Because it works. And how do people know it works? They look around and see it working. It’s only we non-Nordics who need international surveys for proof.

Sadly, the UK – which includes Scotland – is obsessed with ‘measurement and accountability’. Central government ‘s craving for statistical evidence of progress infects local government with the same craving. Local authorities then pass on the paranoia to schools, where senior managers pass it on to teachers, and teachers pass it on to the children and young people in their classes.

And, perhaps most sadly of all, it is also communicated to the parents of tiny children, who come to believe that the sooner their offspring climb on to the data-based treadmill, the more ‘successful’ they will be.

The tests don’t work

Despite the publication of Realising the Ambition (see last month’s blog), Scotland’s politicians still feel the need to monitor early years education through data-gathering about school subjects. For the last few years, we’ve had the Scottish National Standardised Assessments (SNSAs) throughout primary and early secondary school. And they start in P1.

Quite apart from the damage this educational surveillance culture does to the younger generation’s mental health, the data-driven quest for ‘continual improvement’ leads to a plethora of magic-bullet recipes for scoring well in assessments (which are generally only magical in the extent to which they line the pockets of publishers and multinational corporations). So while Scotland is clearly on the side of the angels in rejecting results-by-algorithm at secondary level, we’re still aping the Angles by assessing four- and five-year-olds’ literacy and numeracy skills.

The main objection to national standardised assessment was summed up on Twitter this week, in the words of a frustrated educationist back in 1898:

Once national standardised assessment is established, it becomes the driving force behind education – and, in the end, schools become little more than ‘exam factories‘.

However, now the COVID crisis has shown what statisticians actually do with the information schools diligently produce, and the way it further disadvantages the disadvantaged, there really is no excuse for laying such store by this system.

I’m praying John Swinney’s U-turn on teacher assessment for this year’s secondary exams signals a significant change in the ethos of Scottish education. Curriculum for Excellence is a wonderful vision but hasn’t yet been realised. Realising the Ambition provides an opportunity to get it right from the very beginning of the educational process. The time is ripe for change.

Perhaps the COVID assessment crisis will help open political eyes and henceforth the emphasis in Scottish education will be – at every stage – on supporting teachers to support every student to reach their full potential. As opposed to teaching them to jump through hoops for bureaucrats.

Sue Palmer, Chair of Upstart Scotland