Part One of a two-part blog series, presenting a public health perspective on school starting age and why parents’ views should be central to decision-making, by Diane Delaney

Public health is a globally recognised concept, and the term is on the tip of everyone’s tongue currently with the Covid 19 pandemic. There is a growing understanding that public health is not about individuals, it’s about everyone in the affected population. Measures adopted to defeat the pandemic are about working together for the benefit of one another.

Public health is a globally recognised concept, and the term is on the tip of everyone’s tongue currently with the Covid 19 pandemic. There is a growing understanding that public health is not about individuals, it’s about everyone in the affected population. Measures adopted to defeat the pandemic are about working together for the benefit of one another.

This approach has been adopted for decades to tackle a number of health challenges (i.e. seat belts being worn in cars, the smoking ban, minimum pricing on alcohol). Historically Public Health has been aligned with health and medicine. However, we now understand that health and social needs are interlinked and the social drivers or determinants of health need to be tackled as a priority.

In Scotland, for instance, the Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) successfully adopted a Public Health approach to tackle violence and crime. It wasn’t an automatic success – public sector authorities and others had to be convinced that crime and violence were underpinned by the many social factors impacting the lives of specific population groups. However, over time the VRU’s vision was shown to work and the approach has been accepted. There is still work to do, but changing the perspective of multiple organisations in Scotland to accept that violence can be viewed through a public health lens was a remarkable and welcome innovation.

Public health and young children

The newly formed Public Health Scotland set out their priorities under their public health reform in 2018. The reform focuses on ‘Early Years and Mental Health/Well-being’ as two areas out of six priorities, and children as a population group fall within both of these categories.

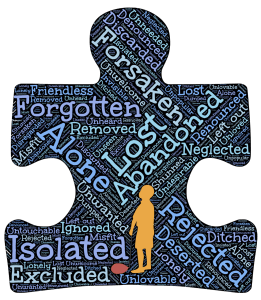

However, in the view of many parents, current policies prevent the fulfilment of the aims of the Scottish Government to ensure children flourish in their early years and that everyone is supported to have good mental health and well-being. Forcing a child to start primary education at age four (when a parent has asked for help and support to provide the child with another year of learning, care and support in an Early Years setting) means that child may struggle to flourish or maintain good mental health and well-being.

However, in the view of many parents, current policies prevent the fulfilment of the aims of the Scottish Government to ensure children flourish in their early years and that everyone is supported to have good mental health and well-being. Forcing a child to start primary education at age four (when a parent has asked for help and support to provide the child with another year of learning, care and support in an Early Years setting) means that child may struggle to flourish or maintain good mental health and well-being.

As a parent and campaigner for the Give Them Time campaign, alongside my experience in interviewing parents for my Masters Dissertation on Public Health, I have heard and read countless stories from parents about the reasons why they want to defer their child’s start in Primary 1. All are consistent with the values underpinning the Public Health reform priorities.

We have so much evidence already about the importance of attachment, love, security and protection from trauma for children, especially during those early years. Yet parents, publicly and privately, have disclosed to Give Them Time campaigners (and myself via interviews) the impact of sending their four-year-olds to school when they were not ready. Many parents feel regret and guilt and, as children grow older, they also reflect on the difficulties they endured being the youngest and sometimes the most immature in their class.

Increasing attention is paid to the mental health of children as a result of recent statistics reflecting that mental ill health is increasing, with one in ten Scottish children having a diagnosable condition. These statistics include children in primary school, a small percentage of which are in Primary 1. Schools are responsible for social and emotional well-being as well as educational attainment. Disturbingly, as of 3rd September 2020 the UK is classified 27th overall in the UNICEF childhood well-being league of 41 countries. This is a significant concern given that we were ranked 16th in 2013.

Increasing attention is paid to the mental health of children as a result of recent statistics reflecting that mental ill health is increasing, with one in ten Scottish children having a diagnosable condition. These statistics include children in primary school, a small percentage of which are in Primary 1. Schools are responsible for social and emotional well-being as well as educational attainment. Disturbingly, as of 3rd September 2020 the UK is classified 27th overall in the UNICEF childhood well-being league of 41 countries. This is a significant concern given that we were ranked 16th in 2013.

The UNICEF report makes clear that well-being is not embedded enough in our policies and practice and children are the victims of this. Notably, where countries are ranked higher, children are older when they start formal schooling.

A public health perspective needs to be adopted for school starting age and transition from early years settings to formal education. Health and social needs cannot be separated and neither of these disappears when a child begins their journey of learning and development in nursery and school. If (when?) Upstart succeeds in establishing a Nordic-style kindergarten stage for three- to seven-year-olds, the problems involved in school deferral will disappear. In the meantime, Give Them Time will continue to support parents whose views are dismissed by their local authority.

Postcode lottery, pedagogical chaos, ‘P1 tests’…

It is a parent’s legal right and duty to decide when their child should be educated and where this occurs, yet, parents cannot use this legal right if they cannot afford to defer. Only two local authorities in Scotland (Falkirk and Highland) value and trust parents enough to provide automatic funding for every child who has a legal right to be deferred requiring more time in an Early Years setting. This is because the Early Years professionals who influence policy in these regions have a deep understanding of child development and learning.

Over recent years, debates about Primary 1 practice have contributed to the adoption of a play-based pedagogical approach in an increasingly number of P1 classrooms across the country. But, although this approach is recognised as crucial to the well-being of this age group, play pedagogy is not compulsory in schools and is at the discretion of local authorities and even individual schools. This means that not only is parents’ ability to defer their child’s school start a postcode lottery (because local authority policies on discretionary funding of deferral vary across Scotland) but access to play-based learning within local authorities is also arbitrary.

years, debates about Primary 1 practice have contributed to the adoption of a play-based pedagogical approach in an increasingly number of P1 classrooms across the country. But, although this approach is recognised as crucial to the well-being of this age group, play pedagogy is not compulsory in schools and is at the discretion of local authorities and even individual schools. This means that not only is parents’ ability to defer their child’s school start a postcode lottery (because local authority policies on discretionary funding of deferral vary across Scotland) but access to play-based learning within local authorities is also arbitrary.

Add to this that the Scottish National Standardised Assessments of literacy and numeracy in Primary 1 create tensions between children and their families. Many parents feel pressure to push their child to achieve academically, which detrimentally affects the health and well-being of both the child and the family. The evidence is clear that the outcomes for children who are subjected to sustained stress and anxiety are not positive.

Seeing education through a ‘public health lens’

This is why I argue that we need to push for a public health perspective in education: we need to look at the bigger picture of the health and well-being of our children, particularly during the early, most formative years of their lives; we need to lobby local and national government decision-makers and leaders to change their policies to reflect the current Public Health priorities; we need to make sure all Early Years practitioners understand their roles and responsibilities for supporting children and families with assessments underpinned by health and well-being (not academia!) and we need to ensure every school can deliver play-based learning in P1, with children outdoors as much as possible.

Regardless of your role, if you are interested in the well-being, education and the future for children, please support the Give Them Time Campaign by writing to politicians, councillors and leaders in Education. If a local authority does not fund all deferrals, ask why. If a school doesn’t deliver play-based learning, ask why. And if children are not outdoors playing and learning in an educational setting, again ask why.

Our Nordic neighbours allow their children to play, have fun and build their skills and learning in a developmentally-appropriate way till they are six or seven – and there is no shortage of academic achievement in those parts of the world. More importantly, child health and well-being is rated significantly higher in all the Nordic countries than in Scotland. Flourishing in the early years and good mental health are priorities for children and they are achievable.

Please, local authorities, ‘Give Them Time’ when their parents request deferral.

You can follow Give Them Time on Twitter at @GiveTimeScot and visit its parent support Facebook page (Deferral Support Scotland)