by Sue Palmer

‘WHY?’ I breathe wearily, retrieving Rabbit for the umpteenth time. ‘WHY do babies do this, over and over again?’ Nine-month-old Maggie beams her delight at reunion with Rabbit … then flings him back to the ground and peers down with interest to see where he’s landed.

That’s when I realise. My granddaughter, bless her, is discovering gravity.

One of the first books I ever read about child development (The Scientist in the Crib, Gopnik et al, 1999) compares babies’ behaviour to scientific method. It explains how every human child, dragged from the comfort of the womb into a completely unknown physical world, is primed to suss out how that world works through trial and error. For a wee one who’s currently desperate to walk, appreciation of the power of gravity is clearly of interest.

Maggie’s experiment with Rabbit probably covers lots of other unconscious learning too, such as the fact that her caring adults love her enough to keep retrieving the wretched bunny. Young children are busy every minute of the day refining the knowledge, skills and capacities biology has primed them to develop. As I’ve learned more about child development over the last twenty years, it’s been horrifying to think how much I took early childhood learning for granted as a parent, teacher, and specialist in literacy teaching.

Development, development, development

Unfortunately, most people haven’t been lucky enough to learn about child development so they still take early childhood learning for granted, and the work of early years practitioners is hugely undervalued and under-rewarded. EYPs know how to observe, intuit, provide loving support and create environments in which each child can learn as appropriate to their developmental needs.

Unfortunately, most people haven’t been lucky enough to learn about child development so they still take early childhood learning for granted, and the work of early years practitioners is hugely undervalued and under-rewarded. EYPs know how to observe, intuit, provide loving support and create environments in which each child can learn as appropriate to their developmental needs.

Political and educational establishments often take child development for granted too. Despite evidence that the poverty-related attainment gap is well-established by the time children are five years old1, Scotland’s National Improvement Framework (NIF) doesn’t collect data on the social, emotional, physical and cognitive aspects of development that influence children’s learning at that age.

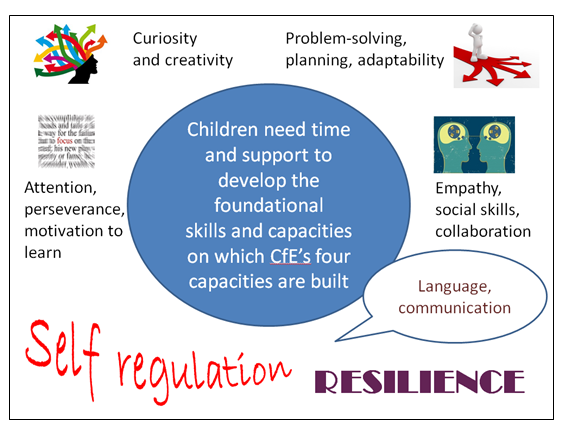

For a recent educational conference, I made a PowerPoint slide (above left) listing some of the skills and capacities involved. Most children can be expected to develop these by age seven or eight, as long as they’ve had the best type of support and experiences in the preceding years – and that means relationship-centred, play-based support, tailored to their personal developmental level, including lots of opportunities for active, social outdoor play.

This sort of provision works wonders in Finland and Estonia, where formal schooling doesn’t start until age seven. They have enviable records of educational achievement and high levels of health and wellbeing. A developmental approach for the under-sevens would benefit all Scottish children too – although the children who’d benefit most, of course, are those whose from disadvantaged backgrounds. It’s why Upstart has always maintained that the way to close the attainment gap (and promote long-term mental health) is to focus on children’s holistic development in the early years, not on age-related standards of educational achievement.

Data, data, data

For policy wonks, the old mantra ‘education, education, education’ is now synonymous with ‘data, data, data’. And the NIF’s data-gathering on the three Rs (reading, writing and ‘rithmetic) begins when children are five, because that’s the school starting age in Scotland. Upstart warned them back in 2015 that homing in on the three Rs at such a young age wouldn’t close the attainment gap, but would very probably exacerbate mental health problems among children. The evidence over the last seven years suggests we were right – and the pandemic has now made both problems much worse.

For policy wonks, the old mantra ‘education, education, education’ is now synonymous with ‘data, data, data’. And the NIF’s data-gathering on the three Rs (reading, writing and ‘rithmetic) begins when children are five, because that’s the school starting age in Scotland. Upstart warned them back in 2015 that homing in on the three Rs at such a young age wouldn’t close the attainment gap, but would very probably exacerbate mental health problems among children. The evidence over the last seven years suggests we were right – and the pandemic has now made both problems much worse.

Yet even though the NIF has recently been advised by the OECD and the Muir Report (‘Putting Learners at the Centre’) that Scotland should gather data on wider aspects of learning and well-being, they still haven’t grasped that, in the early years, this means developmental data. The current NIF consultation on ‘Enhanced Data Collection‘ about the attainment gap proposes no assessment of child development beyond the 27-30 month checklist (which is widely regarded as unreliable evidence because it’s filled in by parents, most of whom know as little about child development as the NIF).

There is a brief mention in the consultation document that the NIF is ‘exploring options to gain better insight into the views and priorities of staff in school and early learning settings.’ ‘Exploring options to gain better insight’ sounds rather like Maggie’s experiments with Rabbit…. But Scotland’s children can’t wait for civil servants to gain insights by trial and error. The attainment gap widens by the hour… and what about the distress of all those children with developmental problems whose lives will probably be blighted by inadequate support…?

The right sort of data

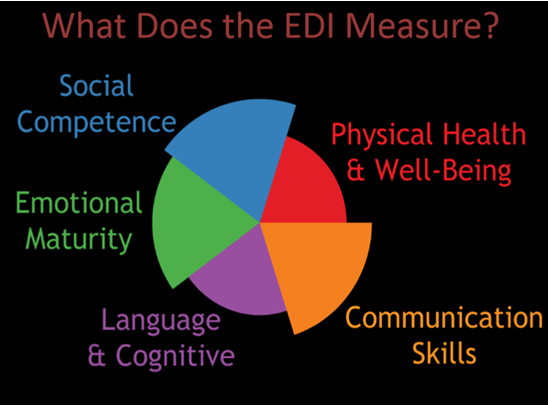

The irony is that a highly reliable developmental assessment tool for P1 has already been validated for use in Scotland. The EDI (Early Development Instrument), is used across Canada and Australia to assess five-year-olds’ physical health/well-being, social competence, emotional maturity, communication skills and language/cognitive skills.

The irony is that a highly reliable developmental assessment tool for P1 has already been validated for use in Scotland. The EDI (Early Development Instrument), is used across Canada and Australia to assess five-year-olds’ physical health/well-being, social competence, emotional maturity, communication skills and language/cognitive skills.

The EDI is completed by P1 teachers towards the end of the first term, when they have got to know the children. This ensures teachers (and primary head teachers) are alerted to developmental factors relevant for children’s future progress in school – much more useful at this age than information about literacy and numeracy skills. But its main function is to provide copious data on which local authorities can base targeted family support during children’s pre-school years.

East Lothian, where the EDI was trialled, was so impressed by the data it provided that they paid to administer it again a couple of years later.

The East Lothian trial took place as the NIF was being established and information about EDI was presented to the Scottish government in 2015. We can only assume NIF policy-makers failed to adopt it because they didn’t know what really matters for that age group.

But better late than never. If any of those earnest NIF seekers-after-wisdom come exploring near you, please tell them about the EDI. If they want more information there’s a whole chapter in Play is the Way, which they can buy via www.upstart.scot.

Even better, please could you find time to fill in their consultation document, and let them know about (a) the significance of child development in the attainment gap and (b) EDI. Not only might this help them close the gap, but it could influence the health, well-being and educational success of countless Scottish children… and thus the future health and well-being of Scotland itself.

1 In ‘Closing the Attainment Gap in Scottish Education’ (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2014), Sosu and Ellis recorded a 13 month gap in vocabulary development and an 11 month gap in problem-solving skills between children from low and high income homes.