by Chloè Beattie

Throughout my career in the early years, I’ve always been fascinated by children’s literacy development. Recently, I’ve studied the development of pre-writing skills for my final uni studies. This is where I began to face true realities and developed a real passion for giving children time to develop skills needed for writing. The early level within the Curriculum for Excellence is between three to six years old (end of Primary One) so why do children face pressure to be able to write before starting school? According to Suzanne Zeedyk1, we need to change our culture around play and expectations of children, such as being able to write their name before Primary One.

Throughout my career in the early years, I’ve always been fascinated by children’s literacy development. Recently, I’ve studied the development of pre-writing skills for my final uni studies. This is where I began to face true realities and developed a real passion for giving children time to develop skills needed for writing. The early level within the Curriculum for Excellence is between three to six years old (end of Primary One) so why do children face pressure to be able to write before starting school? According to Suzanne Zeedyk1, we need to change our culture around play and expectations of children, such as being able to write their name before Primary One.

At times I’ve felt guilty and pondered over the question of children being able to write before they leave nursery. I remember a few years ago being told that as practitioners, we should not ‘teach’ children to write, but yet there continues to be a sense of pressure to teach children to at least write their name, especially in the last term. I’ll admit that on many occasions, I’ve asked a child to write letters with a pen, repeatedly asking them to “try and copy the letters in your name“. You know the famous drawing dots and tracing over again and again and again? But were the children even aware of what letters they were writing? And how did this make them feel? Pressured? Unsure? Anxious in case they didn’t do it right? We should never make children feel this way!

At times I’ve felt guilty and pondered over the question of children being able to write before they leave nursery. I remember a few years ago being told that as practitioners, we should not ‘teach’ children to write, but yet there continues to be a sense of pressure to teach children to at least write their name, especially in the last term. I’ll admit that on many occasions, I’ve asked a child to write letters with a pen, repeatedly asking them to “try and copy the letters in your name“. You know the famous drawing dots and tracing over again and again and again? But were the children even aware of what letters they were writing? And how did this make them feel? Pressured? Unsure? Anxious in case they didn’t do it right? We should never make children feel this way!

Too much too young?

Many authors (such as Palmer and Bayley2, Bruce, Meggit, et al.3) share concern within their publications about the growing pressure that children, notably boys, may experience when forced to write, including ‘painful associations’4. Rudolf Steiner made a powerful argument on this subject. He believed that children who face unnecessary pressure to achieve academically grow to dislike more formal learning and are unmotivated to develop new skills in their later life5.

These reflections made me delve deeper into the ‘biological’ side of children’s development and I came across an x-ray of a six-year-olds’ hand ( see image on left6), where the caption describes the bones in the wrist as ‘still developing’. The image, alongside reflections from literature, reinforced my question, ‘Why are we forcing young children under the age of seven to write?’

These reflections made me delve deeper into the ‘biological’ side of children’s development and I came across an x-ray of a six-year-olds’ hand ( see image on left6), where the caption describes the bones in the wrist as ‘still developing’. The image, alongside reflections from literature, reinforced my question, ‘Why are we forcing young children under the age of seven to write?’

I’ve shared the image with colleagues and families in our setting, aiming to change views around the need for children to be able to write before they go to Primary One. Hopefully, it will take some pressure away from practitioners and parents if they keep this image in mind and know that those wee bones are still growing.

Just Playing?

We know that the early years are the most important years of life, and as practitioners, we value play for what play is. But there are many stereotypes around play and, as Suzanne Zeedyk says in Play is the Way, many people believe play is only beneficial if children are ‘learning’. However, later in the book, Marguerite Hunter Blair states that what we call ‘just playing’ is, in fact, ‘key to healthy growth and holistic  development’.7

development’.7

Over a hundred years ago, Edmund Burke Huey, author of The Psychology and Pedagogy of Reading (1908), suggested that children need to seek out more play-based experiences, rather than formal learning, until their eighth birthday8. He advocated the importance of learning through nature and allowing children to develop at their own pace, highlighting the need for experiences that promote gross motor skills and muscle strength, which are essential skills needed for writing. This emphasis on the importance of active outdoor experiences until the age of around seven is echoed by Froebel, Montessori, Steiner and other international authorities on early learning9.

What’s more, the UNCRC (soon to be written into Scots law) states that parties should recognise ‘the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts’10. So children have a right to the playful, age-and-stage-appropriate activities that are essential for developing skills needed for writing.

Learning from others

Other countries do not expect children to write at such an early age. Magnusson, Hofslundsengen, et al. give an example of a study that draws upon practice in early years settings within Nordic countries11. The article reveals that practitioners will provide children with opportunities to practise language, social and fine motor skills in their daily play, but it’s not until the age of six or seven that children begin to participate in more formal learning such as writing. Palmer speaks highly of Nordic countries such as Finland, where play-based kindergartens are fully implemented and give the children time within the early years to shine and excel in skills needed for literacy and all other areas of development12.

Other countries do not expect children to write at such an early age. Magnusson, Hofslundsengen, et al. give an example of a study that draws upon practice in early years settings within Nordic countries11. The article reveals that practitioners will provide children with opportunities to practise language, social and fine motor skills in their daily play, but it’s not until the age of six or seven that children begin to participate in more formal learning such as writing. Palmer speaks highly of Nordic countries such as Finland, where play-based kindergartens are fully implemented and give the children time within the early years to shine and excel in skills needed for literacy and all other areas of development12.

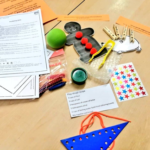

Occupational therapists are experts in the development of motor skills. Through reading and and working in partnership with occupational therapists, my knowledge of pre-writing skills has significantly broadened. However, the importance of working with families and sharing the message of ‘play is the way’ continues. Due to my reflections and ideas for sharing the importance of play for writing, I created a ‘Little Scribblers’ pack for children and families to use at home. The packs (see image on right) allow children to develop these skills at home and include helpful information from NHS Tayside Occupational Therapy.

Occupational therapists are experts in the development of motor skills. Through reading and and working in partnership with occupational therapists, my knowledge of pre-writing skills has significantly broadened. However, the importance of working with families and sharing the message of ‘play is the way’ continues. Due to my reflections and ideas for sharing the importance of play for writing, I created a ‘Little Scribblers’ pack for children and families to use at home. The packs (see image on right) allow children to develop these skills at home and include helpful information from NHS Tayside Occupational Therapy.

As practitioners, we can facilitate experiences that develop writing skills within everyday practice. There’s no reason to print off worksheets or draw those dots on a page. Many resources for pre-writing can be found in the world around us. For example, climbing trees and balancing across logs can help promote muscle strength, balance, and hand-eye co-ordination. Sticks and mud can be used as tools for mark-making. Helping to hang up washing with pegs or rinsing out socks can develop those little muscles in the hands and fingers and a pincer grasp.

Children need time. They need time to play, to love, to trust, to enjoy childhood and to most importantly to have fun!

References

1 ZEEDYK, S., (2021). Relationships, Play and Learning in Scottish Identity. In: Palmer, S, ed., Play is The Way. 2nd ed. Paisley: CCWB Press. pp.19-32.

2. PALMER, S. and BAYLEY, R., (2013). Foundations of Literacy- a Balanced Approach to Language, Listening and Literacy Skills in The Early Years. 4TH ed. London: Featherstone.

3. BRUCE, T., MEGGIT, C. and GRENIER, J., (2010). Childcare and Education. 5th ed. London: Hodder Education.

4. Palmer and Bayley above, p.86.

5. POUND, L., (2008). How Children Learn- Book 2. London: MA Education Ltd.

6. AJ PHOTO., (Undated). Child’s Hand X-Ray. Available: https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/302583/view/child-s-hand-x-ray. [Date Accessed 2nd March 2022].

7 PALMER, S, ed., Play is The Way. 2nd ed. Paisley: CCWB Press p20, p31

8. Pound, see 5 above

9. ELKIND, D Giants in the Nursery: A Biographical History of Developmentally Appropriate Practice. Redleaf Press, St Paul MN (2015)

10.See (Undated). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. London: UNICEF UK. Available here. [Date Accessed: 21st March 2022].

11. MAGNUSSON, M., HOFSLUNDSENGEN, H., JUSSLIN, S., MELLGREN, E., SVENSSON, A. K., HEILÄ-YLIKALLIO, R. and HAGTVET, B. E., (2021). Nordic Preschool Student Teachers’ Views on Early Writing in Preschool. International Journal of Early Years Education. ‘Online First’ Published 8TH July 2021. [Available from: DOI:10.1080/09669760.2021.1948820].

12 PALMER, S, ed., Play is The Way. 2nd ed. Paisley: CCWB Press. pp.87-9