Part Two of a two-part blog series, presenting a public health perspective on school starting age and why parents’ views should be central to decision-making, by Diane Delaney

I have just submitted my Masters in Public Health dissertation on the subject of parents’ views and experiences when they felt obliged to send their four-year-old child to school. I have no professional experience in education – my background is in health and social work. But when my own child was expected to start school at four years old, I suddenly felt an urge to understand more about learning, development and transitions for children moving on from early years settings.

I have just submitted my Masters in Public Health dissertation on the subject of parents’ views and experiences when they felt obliged to send their four-year-old child to school. I have no professional experience in education – my background is in health and social work. But when my own child was expected to start school at four years old, I suddenly felt an urge to understand more about learning, development and transitions for children moving on from early years settings.

My own experience of my child’s transition to primary school seemed the perfect opportunity to use scientific methods to investigate this significant milestone in all children’s lives.

POLICY VS REALITY

There’s plenty of policy and research in Scotland pertaining to the needs and well-being of children. The Scottish Government has produced a multitude of policy documents and legislation to ensure children and young people are protected and nurtured – and the commitment of the Scottish Parliament to incorporate the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child into Scots law is a powerful reflection of our country’s commitment.Local governments reflect this national aspiration. Their websites are awash with messages to parents that their contributions about their children’s needs are necessary and worthwhile.

There’s plenty of policy and research in Scotland pertaining to the needs and well-being of children. The Scottish Government has produced a multitude of policy documents and legislation to ensure children and young people are protected and nurtured – and the commitment of the Scottish Parliament to incorporate the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child into Scots law is a powerful reflection of our country’s commitment.Local governments reflect this national aspiration. Their websites are awash with messages to parents that their contributions about their children’s needs are necessary and worthwhile.

So there’s no shortage of policy rhetoric about children’s well-being/welfare and about parents being partners with public authorities in relation to this. But, in terms of children under six years old, the scientific evidence base doesn’t back up this rhetoric. There’s little research that addresses issues affecting children from a parent’s perspective, particularly in relation to education, transitions and the early years population. And most of the current evidence base regarding well-being surrounds the mental health of adolescents/ teenagers and young adults, with very limited interest in the mental health and well-being of four-year-old children in Scotland

FOLLOWING THE EVIDENCE

The rationale for my study was based on these gaps in the evidence. I put social media adverts on Twitter and Facebook, inviting participation from parents who were concerned about the well-being of their four-year-old child transitioning to primary school. Then I used thematic analysis to understand and interpret their experiences. The mums who volunteered to be interviewed were aged 35-45, living in Central Scotland, with between two and five children. Four were in professional/ skilled jobs with one unknown.

The children discussed were born in the months of November, December and January and were all aged four when they started school. The parents had sent these children to school despite being concerned about the transition process.

My findings revealed a number of issues within the early years sector. The first was that early years (EY) practitioners were generally unable to provide parents with accurate information about their rights as with regards to education (deferral).The second was that parents who raised concerns with EY practitioners felt dismissed, resulting in feelings of powerlessness, which led to their concerns being amplified.

In these circumstances, parents found the burden of decision-making stressful, which was compounded by actual or perceived societal pressures to conform to the norm of sending your child to school in the year s/he turned five. If you didn’t conform, the assumption was that there was ‘something wrong’ with your child. No parent wanted such a label or stigma attached to them or their child. They told me that the early years practitioners did not dispel these misinformed societal beliefs and, in some cases, appeared to endorse this view. It wasn’t clear from my study why the practitioners were unable to provide the correct information and support to parents. I believe this requires further investigation in the future.

In these circumstances, parents found the burden of decision-making stressful, which was compounded by actual or perceived societal pressures to conform to the norm of sending your child to school in the year s/he turned five. If you didn’t conform, the assumption was that there was ‘something wrong’ with your child. No parent wanted such a label or stigma attached to them or their child. They told me that the early years practitioners did not dispel these misinformed societal beliefs and, in some cases, appeared to endorse this view. It wasn’t clear from my study why the practitioners were unable to provide the correct information and support to parents. I believe this requires further investigation in the future.

Despite parents raising concerns about their children’s well-being, there were no tailored transition plans. All children (whatever their age – and, at four/five the difference of the oldest and the youngest amounts to a quarter of a lifetime) visited the primary schools in groups. Neither parents nor children contributed to the transition plan. Parents did not have the opportunity to speak to Primary 1 (P1) teachers about their concerns. As a result, their child transitioned to school without the P1 teacher having any knowledge of their concerns.

Many parents are concerned about the well-being of a child who is suddenly thrust into a school environment at four years old – and my research suggested that these concerns are warranted. The parents in my study described a significant impact on their child’s well-being, especially their emotional well-being, throughout P1. For some parents, concerns about their child’s well-being have continued and many have reflected on the potential longer term impact of sustained stress during P1 – including their child adopting a self-depreciating attitude as a result of comparing themselves to others in a negative manner.

A PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACH

I believe that – due to Scotland’s ridiculously early school starting age – our education sector is locked into a mistaken approach to the health, well-being and education of young children. Instead we need a public health approach to early years in order to ensure the promotion and protection of child well-being.

I believe that – due to Scotland’s ridiculously early school starting age – our education sector is locked into a mistaken approach to the health, well-being and education of young children. Instead we need a public health approach to early years in order to ensure the promotion and protection of child well-being.

It is well documented that early childhood (defined by the UNCRC as birth to eight) is one of the most important stages of life, during which children require love, attachment, nurturing and a sense of safety.

Due to growing interest in Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) in Scotland, there is increased recognition of the impact of toxic stress, and unanimous agreement that children should be protected from this. Public Health Scotland has made ‘early years’ and ‘children’s mental health’ priority areas as part of their reform.

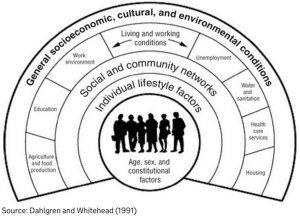

In order to achieve these Public Health ambitions, the Scottish government should re-consider the age at which children transfer from nursery to primary school, in the context of health and well-being of the child. There is already a solid understanding that children’s health and well-being is predicated by a multitude of factors reflected in Dahlgren and White’s Social Determinants of Health Model1. These include education, housing conditions, employment status, health, disability, age, sex, gender, income etc.

In order to achieve these Public Health ambitions, the Scottish government should re-consider the age at which children transfer from nursery to primary school, in the context of health and well-being of the child. There is already a solid understanding that children’s health and well-being is predicated by a multitude of factors reflected in Dahlgren and White’s Social Determinants of Health Model1. These include education, housing conditions, employment status, health, disability, age, sex, gender, income etc.

None of these factors were considered for any of the parents in my study when their child was three years old. Perhaps more importantly, the role and value of parents as the adults responsible for the education and welfare of their child was disregarded.

We need a societal shift in attitude and culture to empower parents as the responsible decision-makers for their child’s welfare and education. EY practitioners also need training to be able to support parents in this process and to understand the law and policy in this area. Courageous leadership is key to change both politically and organisationally and we need this urgently now in the light of the recent UNICEF report card on child wellbeing

What’s needed is a more tailored approach to transition processes, inclusion of children and families’ perspectives, and awareness in primary schools of parents’ concerns pre-transition (with increased opportunities for parents to communicate with teachers before, during and after their children enter P1). Alongside this, parents must be empowered to use their legal right to defer and this should not be determined by their ability to pay for nursery fees.

What’s needed is a more tailored approach to transition processes, inclusion of children and families’ perspectives, and awareness in primary schools of parents’ concerns pre-transition (with increased opportunities for parents to communicate with teachers before, during and after their children enter P1). Alongside this, parents must be empowered to use their legal right to defer and this should not be determined by their ability to pay for nursery fees.

Maree Todd, the Minister for Children and Young People, confirmed on 15th September 2020 that legislation will be introduced before the end of the parliamentary term to ensure funding for all children whose parents wish them to attend an additional year in nursery. But many of the parents in my study were in favour of Scotland to adopting a kindergarten stage – like many other countries globally – to ensure play and fun is at the heart of learning and development for all children till they are six or seven years old. To get it right for every child, Scotland needs to ensure fairness for all children, with well-being firmly placed at the heart of any process, including transition to primary school.

(1) Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. (1991) Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Stockholm, Sweden: Institute for Futures Studies.